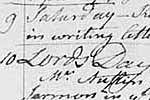

The Lord's Prayer in Jefferson's Hand

The Lord's Prayer in Jefferson's Hand

Jefferson liked to experiment with and use cryptology. There are several different codes in his

papers at the Library of Congress, including this one based on the Lord's Prayer, which

Jefferson carefully wrote out as a block of consecutive letters.

The Lord's Prayer

Thomas Jefferson, Holograph manuscript

Manuscript Division, Library of Congress (161)

The Jefferson Bible

It is thought that Jefferson prepared what is referred to as the "Jefferson Bible" in 1820. In

this volume, Jefferson used excerpts from New Testaments in four languages to create parallel

columns of text recounting the life of Jesus, preserving what he considered to be Christ's

authentic actions and statements, eliminating the mysterious and miraculous. He began his

account with Luke's second chapter, deleting the first in which the angel Gabriel announced to

the Virgin Mary that she would give birth to the Messiah by the Holy Spirit. On the pages

seen here, Jefferson deleted the part of the birth story in which the angel of the Lord appeared

to the shepherds. The text ends with the crucifixion and burial and omits any resurrection

appearance.

![The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth [index]](vc6799th.jpg)

The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth extracted

textually from

the Gospels in Greek, Latin, French & English

[index page one] --

[index page two] --

[index page three]

Thomas Jefferson, c. 1820

National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution (162a)

![The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth [title page]](vc6419th.jpg)

The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth extracted

textually from

the Gospels in Greek, Latin, French & English.

[title page] -

[page one] -

[page two]

Thomas Jefferson.

Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1904

General Collections, Library of Congress (162c)

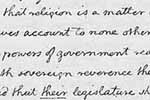

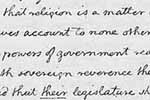

A Wall of Separation

A Wall of Separation

The celebrated phrase, "a wall of separation between church and state," was contained in

Thomas Jefferson's letter to the Danbury Baptists. American courts have used the phrase to

interpret the Founders' intentions regarding the relationship between government and religion.

The words, "wall of separation," appear just above the section of the letter that Jefferson

circled for deletion. In the deleted section Jefferson explained why he refused to proclaim

national days of fasting and thanksgiving, as his predecessors, George Washington and John

Adams, had done. In the left margin, next to the deleted section, Jefferson noted that he

excised the section to avoid offending "our republican friends in the eastern states" who

cherished days of fasting and thanksgiving.

Thomas Jefferson to Nehemiah Dodge, Ephraim Robbins and Stephen S. Nelson,

a committee of the Danbury Baptist Association in the state of Connecticut, January 1, 1802.

Holograph draft letter, 1802

Jefferson Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress (163a)

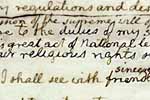

The Danbury Baptist Letter, as Originally Drafted

The Danbury Baptist Letter, as Originally Drafted

The Library of Congress is grateful to the Federal Bureau of Investigation Laboratory for

recovering the lines obliterated from the Danbury Baptist letter by Thomas Jefferson. He

originally wrote "a wall of eternal separation between church and state," later deleting the

word "eternal." He also deleted the phrase "the duties of my station, which are merely

temporal." Jefferson must have been unhappy with the uncompromising tone of both of these

phrases, especially in view of the implications of his decision, two days later, to begin

attending church services in the House of Representatives.

Thomas Jefferson to Nehemiah Dodge, Ephraim Robbins and Stephen S. Nelson,

a committee of the Danbury Baptist Association in the state of Connecticut, January 1, 1802.

Letter, digitally revised to expose obliterated sections. Copyprint

Manuscript Division, Library of Congress (163b)

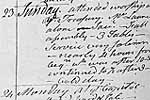

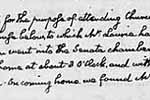

Jefferson at Church in the Capitol

Jefferson at Church in the Capitol

In his diary, Manasseh Cutler (1742-1823), a Federalist Congressman from Massachusetts and

Congregational minister, notes that on Sunday, January 3, 1802, John Leland preached a

sermon on the text "Behold a greater than Solomon is here. Jef[ferso]n was present."

Thomas Jefferson attended this church service in Congress, just two days after issuing the

Danbury Baptist letter. Leland, a celebrated Baptist minister, had moved from Orange County,

Virginia, and was serving a congregation in Cheshire, Massachusetts, from which he had

delivered to Jefferson a gift of a "mammoth cheese," weighing 1235 pounds.

Journal entry, January 3, 1802

Manasseh Cutler

Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Library (164)

![Manasseh Cutler to Joseph Torrey, January 3, 1803. [page one]](vc6760th.jpg)

Jefferson and Family at Church

Manasseh Cutler to Joseph Torrey, January 3, 1803. [page one]

--

[page two] --

[page three] --

[page four]

In this letter Manasseh Cutler informs Joseph Torrey that Thomas Jefferson "and his family

have constantly attended public worship in the Hall" of the House of Representatives.

Manuscript letter

Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Library (165)

![Reminiscences.[right]](vc6521th.jpg)

![Reminiscences.[left]](vc6520th.jpg) Reserved Seats at Capitol Services

Reserved Seats at Capitol Services

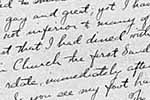

Here is a description, by an early Washington "insider," Margaret Bayard Smith (1778-1844),

a writer and social critic and wife of Samuel Harrison Smith, publisher of the National

Intelligencer, of Jefferson's attendance at church services in the House of Representatives:

"Jefferson during his whole administration was a most regular attendant. The seat he chose

the first day sabbath, and the adjoining one, which his private secretary occupied, were ever

afterwards by the courtesy of the congregation, left for him."

Reminiscences. [left page] -

[right page]

Margaret Bayard Smith, 1837. Manuscript volume. (Copyprint of verso)

Manuscript Division, Library of Congress (166-166a)

Incident at Congressional Church Services

Incident at Congressional Church Services

In this letter Catherine Mitchill, wife of New York senator Samuel Latham Mitchill, describes

stepping on Jefferson's toes at the conclusion of a church service in the House of

Representatives. She was "so prodigiously frighten'd," she told her sister, "that I could not

stop to make an apology, but got out of the way as quick as I could."

Catherine Akerly Mitchill to her sister, Margaret Miller, April 8, 1806.

Manuscript letter

Manuscript Division, Library of Congress (167)

![Abijah Bigelow to Hannah Bigelow, December 28, 1812.[right page]](f0615bth.jpg)

![Abijah Bigelow to Hannah Bigelow, December 28, 1812. [left page]](f0615ath.jpg) Madison Seen at House Church Service

Madison Seen at House Church Service

Abijah Bigelow, a Federalist congressman from Massachusetts, describes President James

Madison at a church service in the House on December 27, 1812, as well as an incident that

had occurred when Jefferson was in attendance some years earlier.

Abijah Bigelow to Hannah Bigelow, December 28, 1812. [left page] -

[right page]

Manuscript letter

The American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Massachusetts (168)

Hymns Played at Congressional Church Service

Hymns Played at Congressional Church Service

According to Margaret Bayard Smith, a regular at church services in the Capitol, the Marine

Band "made quite a dazzling appearance in the gallery . . . but in their attempts to accompany

the psalm-singing of the congregation, they completely failed and after a while, the practice

was discontinued."

"The President's Own" United States Marine Corp Band, ca. 1798.

Watercolor, Lt. Col.

Donna Neary, USMCR, late twentieth century. Copyprint.

United States Marine Corp Band, Washington, D.C. (169)

The Old House of Representatives

The Old House of Representatives

Church services were held in what is now called Statuary Hall from 1807 to 1857. The first

services in the Capitol, held when the government moved to Washington in the fall of 1800,

were conducted in the "hall" of the House in the north wing of the building. In 1801 the

House moved to temporary quarters in the south wing, called the "Oven," which it vacated in

1804, returning to the north wing for three years. Services were conducted in the House until

after the Civil War. The Speaker's podium was used as the preacher's pulpit.

The Old House of Representatives

Oil on canvas by Samuel F.B. Morse, 1822. Copyprint.

In the collection of the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Museum Purchase,

Gallery Fund (170)

A Millennialist Sermon Preached in Congress

A Millennialist Sermon Preached in Congress

This sermon on the millennium was preached by the Baltimore Swedenborgian minister, John

Hargrove (1750-1839) in the House of Representatives. One of the earliest millennialist

sermons preached before Congress was offered on July 4, 1801, by the Reverend David

Austin (1759-1831), who at the time considered himself "struck in prophesy under the style of

the Joshua of the American Temple." Having proclaimed to his Congressional audience the

imminence of the Second Coming of Christ, Austin took up a collection on the floor of the

House to support services at "Lady Washington's Chapel" in a nearby hotel where he was

teaching that "the seed of the Millennial estate is found in the backbone of the American

Revolution."

A Sermon on the Second Coming of Christ, and on the Last Judgment.

Delivered the 25th

December, 1804 before both houses of Congress, at the Capitol in the city of Washington.

John Hargrove. Baltimore: Warner & Hanna, 1805

Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (171)

First Catholic Sermon in the House

First Catholic Sermon in the House

On January 8, 1826, Bishop John England (1786-1842) of Charleston, South Carolina, became

the first Catholic clergyman to preach in the House of Representatives. The overflow

audience included President John Quincy Adams, whose July 4, 1821, speech England

rebutted in his sermon. Adams had claimed that the Roman Catholic Church was intolerant of

other religions and therefore incompatible with republican institutions. England asserted that

"we do not believe that God gave to the church any power to interfere with our civil rights, or

our civil concerns." "I would not allow to the Pope, or to any bishop of our church," added

England, "the smallest interference with the humblest vote at our most insignificant balloting

box."

John England, Bishop of Charleston, South Carolina

Oil on canvas

Diocese of Charleston, Charleston, South Carolina (173)

The substance of a discourse preached in the hall of the House of Representatives

of the United States, January 8, 1826.

John England. Baltimore: F. Lucas, 1826

Rare Book and Special Collections Division,

Library of Congress (172)

Woman Preacher in the House

Woman Preacher in the House

In 1827, Harriet Livermore (1788-1868), the daughter and granddaughter of Congressmen,

became the second woman to preach in the House of Representatives. The first woman to

preach before the House (and probably the first woman to speak officially in Congress under

any circumstances) was the English evangelist, Dorothy Ripley (1767-1832), who conducted a

service on January 12, 1806. Jefferson and Vice President Aaron Burr were among those in a

"crowded audience." Sizing up the congregation, Ripley concluded that "very few" had been

born again and broke into an urgent, camp meeting style exhortation, insisting that "Christ's

Body was the Bread of Life and His Blood the drink of the righteous."

Harriet Livermore.

Engraving by J.B. Longacre, from a painting by Waldo and Jewett, 1827

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution (174)

Communion Service in the Treasury Building

Communion Service in the Treasury Building

Manasseh Cutler here describes a four-hour communion service in the Treasury Building,

conducted by a Presbyterian minister, the Reverend James Laurie: "Attended worship at the

Treasury. Mr. Laurie alone. Sacrament. Full assembly. Three tables; service very solemn;

nearly four hours."

Journal entry, December 23, 1804

Manasseh Cutler. Manuscript

Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Library (175)

The Treasury Building

The Treasury Building

The first Treasury Building, where several denominations conducted church services, was

burned by the British in 1814. The new building, seen here on the lower right, was built on

approximately the same location as the earlier one, within view of the White House.

Washington City, 1820.

Watercolor sketch by Baroness Hyde de Neuville, 1820

I. N. Phelps Stokes Collection, The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art,

Prints and Photographs, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations (176)

Adams's Description of a Church Service in the Supreme Court

Adams's Description of a Church Service in the Supreme Court

John Quincy Adams here describes the Reverend James Laurie, pastor of a Presbyterian

Church that had settled into the Treasury Building, preaching to an overflow audience in the

Supreme Court Chamber, which in 1806 was located on the ground floor of the Capitol.

Diary entry, February 2, 1806

John Quincy Adams. Copyprint

Adams Family Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston (177)

The Old Supreme Court Chamber

The Old Supreme Court Chamber

Description of church services in the Supreme Court chamber by Manasseh Cutler (1804) and John Quincy Adams (1806) indicate that services were held in the Court soon after the

government moved to Washington in 1800.

The Old Supreme Court Chamber, ca. 1810, U. S. Capitol Building

Photograph by Franz Jantzen. Copyprint

Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States (178)

Church Services in Congress after the Civil War

Church Services in Congress after the Civil War

Charles Boynton (1806-1883) was in 1867 chaplain of the House of Representatives and

organizing pastor of the First Congregational Church in Washington, which was trying at that

time to build its own sanctuary. In the meantime the church, as Boynton informed potential

donors, was holding services "at the Hall of Representatives" where "the audience is the

largest in town. . . .nearly 2000 assembled every Sabbath" for services, making the

congregation in the House the "largest Protestant Sabbath audience then in the United States."

The First Congregational Church met in the House from 1865 to 1868.

Fundraising brochure

Charles B. Boynton. Washington, D.C.: November 1, 1867

Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (180)

House of Representatives, After the Civil War

House of Representatives, After the Civil War

The House moved to its current location on the south side of the Capitol in 1857. It contained

the "largest Protestant Sabbath audience" in the United States when the First Congregational

Church of Washington held services there from 1865 to 1868.

The House of Representatives, 1866

Chromo-lithograph by E. Sachse & Co, 1866

Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress (179)

|

Jefferson Attacked as an Infidel

Jefferson Attacked as an Infidel Jefferson's Opinion of Jesus

Jefferson's Opinion of Jesus The Lord's Prayer in Jefferson's Hand

The Lord's Prayer in Jefferson's Hand![The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth [index]](vc6799th.jpg)

![The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth [title page]](vc6419th.jpg)

A Wall of Separation

A Wall of Separation The Danbury Baptist Letter, as Originally Drafted

The Danbury Baptist Letter, as Originally Drafted Jefferson at Church in the Capitol

Jefferson at Church in the Capitol![Manasseh Cutler to Joseph Torrey, January 3, 1803. [page one]](vc6760th.jpg)

![Reminiscences.[right]](vc6521th.jpg)

![Reminiscences.[left]](vc6520th.jpg) Reserved Seats at Capitol Services

Reserved Seats at Capitol Services Incident at Congressional Church Services

Incident at Congressional Church Services![Abijah Bigelow to Hannah Bigelow, December 28, 1812.[right page]](f0615bth.jpg)

![Abijah Bigelow to Hannah Bigelow, December 28, 1812. [left page]](f0615ath.jpg) Madison Seen at House Church Service

Madison Seen at House Church Service Hymns Played at Congressional Church Service

Hymns Played at Congressional Church Service The Old House of Representatives

The Old House of Representatives A Millennialist Sermon Preached in Congress

A Millennialist Sermon Preached in Congress First Catholic Sermon in the House

First Catholic Sermon in the House

Woman Preacher in the House

Woman Preacher in the House Communion Service in the Treasury Building

Communion Service in the Treasury Building The Treasury Building

The Treasury Building

Adams's Description of a Church Service in the Supreme Court

Adams's Description of a Church Service in the Supreme Court The Old Supreme Court Chamber

The Old Supreme Court Chamber Church Services in Congress after the Civil War

Church Services in Congress after the Civil War House of Representatives, After the Civil War

House of Representatives, After the Civil War