HOME

- EXHIBITION OVERVIEW

HOME

- EXHIBITION OVERVIEW

SECTIONS:

I. America as Refuge -

II. 18th Century America

III. American Revolution -

IV. Congress of the Confederation -

V. State Governments

VI. Federal Government -

VII. New Republic

II. Religion in Eighteenth-Century

America

Against a prevailing view

that eighteenth-century Americans had not perpetuated the first

settlers' passionate commitment to their faith, scholars now identify a high level of religious

energy in colonies after 1700. According to one expert, religion was in the "ascension rather

than the declension"; another sees a "rising vitality in religious life" from 1700 onward; a

third finds religion in many parts of the colonies in a state of "feverish growth." Figures on

church attendance and church formation support these opinions. Between 1700 and 1740, an

estimated 75 to 80 percent of the population attended churches, which were being built at a

headlong pace.

Toward mid-century the country experienced its first major religious revival. The

Great Awakening swept the English-speaking world, as religious energy vibrated between

England, Wales, Scotland and the American colonies in the 1730s and 1740s. In America, the

Awakening signaled the advent of an encompassing evangelicalism--the belief that the essence

of religious experience was the "new birth," inspired by the preaching of the Word. It

invigorated even as it divided churches. The supporters of the Awakening and its evangelical

thrust--Presbyterians, Baptists and Methodists--became the largest American Protestant

denominations by the first decades of the nineteenth century. Opponents of the Awakening or

those split by it--Anglicans, Quakers, and Congregationalists--were left behind.

Another religious movement that was the antithesis of evangelicalism made its

appearance in the eighteenth century. Deism, which emphasized morality and rejected the

orthodox Christian view of the divinity of Christ, found advocates among upper-class

Americans. Conspicuous among them were Thomas Jefferson and John Adams. Deists, never

more than "a minority within a minority," were submerged by evangelicalism in the nineteenth

century.

THE APPEARANCE OF

EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY CHURCHES

An Early Episcopal Church

St. James Church, built in South Carolina's oldest Anglican parish outside of Charleston, is

thought to have been constructed between 1711 and 1719 during the rectorate of the Reverend

Francis le Jau, a missionary of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts.

St. James Church, Goose Creek, Berkeley County,

South Carolina, [exterior view] -

[interior view]

Photograph by Frances Benjamin

Johnston (1864-1952), c. 1930

Prints and Photographs Division,

Library of Congress (50-51)

|

Churches in eighteenth-century America came in all sizes and shapes, from the plain, modest

buildings in newly settled rural areas to elegant edifices in the prosperous cities on the eastern

seaboard. Churches reflected the customs and traditions as well as the wealth and social status

of the denominations that built them. Hence, a new Anglican Church in rural Goose Creek,

South Carolina, was fitted out with an impressive wood-carved pulpit, while a fledgling

Baptist Church in rural Virginia had only the bare essentials. German churches contained

features unknown in English ones.

|

Growth of the Eighteenth-Century Church

The growth of the American church in the eighteenth century can be illustrated by changes in

city skylines over the course of the century. These three views of New York City in 1690,

1730, and 1771 display the increased number of the city's churches. An empty vista in 1690

had become a forest of eighteen steeples by 1771. Clearly discernable in the 1730 engraving

are (from left to right) the spires of Trinity Church (Anglican), the Lutheran Church, the

"new" Dutch Reformed Church, the French Protestant Church (Huguenots), City Hall, the

"old" Dutch Reformed Church, the Secretary's Office and the church in Fort George.

Nieuw Amsterdam on the island of Manhattan

Etching, c. 1690. Facsimile

>Geography & Map Division, Library of

Congress (47)

A View of Fort George with the City of New

York

Engraving by I. Carwithan, c. 1730

Geography & Map Division, Library of

Congress (48)

Prospect of the City of New York

Woodcut from Hugh Gaine, New York Almanac, 1771. Copyprint

The American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Massachusetts (49)

Christ Church, Philadelphia

Christ Church, Philadelphia

Christ Church of Philadelphia is an example of how colonial American congregations, once

they became well established and prosperous, built magnificent churches to glorify God.

Enlarged and remodelled, the Christ Church building was completed in 1744. A steeple was

added ten years later. Contemporaries were in awe of the finished house of worship, one

remarking that "it was the handsomest structure of the kind that I ever saw in any part of the

world; uniting in the peculiar features of that species of architecture, the most elegant variety

of forms, with the most chaste simplicity of combination."

A South East view of Christ's Church

Engraving in

Columbian Magazine, November 1787-

December 1787

Philadelphia: 1787

Rare Book and Special Collections Division,

Library of Congress (52)

A Rural Baptist Church

A Rural Baptist Church

The South Quay Baptist Church (top) was founded in 1775, although it was not formally

"organized" until ten years later. The difference between the interior of the rural Mount

Shiloh Baptist Church and its Anglican counterpart, St. James Church, reveals much about the

differences between the denominations that worshiped in each structure.

Exterior of South Quay Baptist Church, Copyprint

Interior of Mt. Shiloh Baptist Church , Copyprint

Virginia Baptist Historical Society (53-54)

Colonial Baptist Church

Colonial Baptist Church

Believed to be the first Baptist church in America, the Providence congregation, founded by

Roger Williams, was organized in 1639. The meeting house, shown here, was constructed in

1774-1775 from plans by architect Joseph Brown, after a design by James Gibbs. This church

shows that some colonial Baptists had no compunctions about erecting imposing church

buildings.

A S.W. view of the Baptist Meeting House, Providence,

R.I.

Engraving by S. Hill for

Massachusetts Magazine

or Monthly

Museum of Knowledge and Rational Entertainment, August 1789

Rare Book and Special Collections Division,

Library of Congress (55)

Lutheran Church Services

Lutheran Church Services

This view of the interior of a Lutheran Church by Pennsylvania folk artist Lewis Miller

(1796-1882) reveals features--wall paintings of great figures of the modern and early

church--which

would have been absent from English Protestant churches of the time. Notice the homey

interruptions to worship in early America such as the sexton chasing a dog out of the sanctuary

and a member stoking a stove.

">

In Side of the Old Lutheran Church in 1800, inYork, Pa.

Watercolor with pen and ink by Lewis Miller, c. 1800

The Historical Society of York County, Pennsylvania (56)

|

DEISM

|

"Deism" is a loosely used term that describes the views of certain English and continental

thinkers. These views attracted a following in Europe toward the latter part of the

seventeenth century and gained a small but influential number of adherents in America in the

late eighteenth century. Deism stressed morality and rejected the orthodox Christian view of

the divinity of Christ, often viewing him as nothing more than a "sublime" teacher of

morality. Thomas Jefferson and John Adams are usually considered the leading American

deists. There is no doubt that they subscribed to the deist credo that all religious claims were

to be subjected to the scrutiny of reason. "Call to her tribunal every fact, every opinion,"

Jefferson advised. Other founders of the American republic, including George Washington,

are frequently identified as deists, although the evidence supporting such judgments is often

thin. Deists in the United States never amounted to more than a small percentage of an

evangelical population.

|

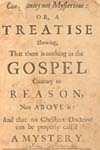

A Deist Tract

A Deist Tract

John Toland (1670-1722) was a leading English deist whose works, challenging the mysteries

at the heart of orthodox Christian belief, found an audience in the American colonies.

Christianity Not Mysterious: or, a Treatise shewing, That

there is nothing in the Gospel

Contrary to Reason, . . . .

John Toland

London: 1696

Rare Book and Special Collections

Division,

Library of Congress (59)

John Locke

John Locke

A famous political philosopher to whose views on the formation of governments most

Americans subscribed,

John Locke (1632-1704) wrote profoundly

important treatises on

religion. His letters on toleration became a bible to many in the eighteenth century, who were

still contending against the old theories of religious uniformity. Locke also argued for the

"reasonableness" of Christianity but rejected the efforts of Toland and other deists to claim

him as their spiritual mentor.

Letter Concerning Toleration

John Locke

London: A. Millar, H. Woodruff, et al., 1765

Rare Book and Special Collections

Division,

Library of Congress (57-58)

|

Bolingbroke's Influence on Thomas Jefferson

Bolingbroke's Influence on Thomas Jefferson

Lord Viscount Bolingbroke (1678-1751), an English deist, was a lifelong favorite of Jefferson.

In his Literary Commonplace Book, a volume compiled mostly in the 1760s, Jefferson copied

extracts from various authors, transcribing from Bolingbroke some 10,000 words, six times as

much as from any other author and forty percent of the whole volume. Young Jefferson was

particularly partial to Bolingbroke's observations on religion and morality.

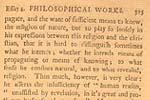

The Philosophical Works of the late Right Honourable

Henry St. John,

Lord Viscount Bolingbroke [left page] -

[right

page]

Henry Saint-John, Viscount Bolingbroke, London: David Mallet, 1754

Rare Book and Special Collections Division,

Library of Congress (60)

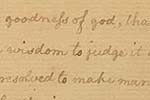

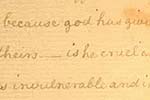

Thomas Jefferson's Literary Commonplace Book

Thomas Jefferson's Literary Commonplace Book

In this part of his Literary Commonplace Book, Thomas Jefferson copied from Bolingbroke's

Works, a passage unfavorably comparing New Testament ethics to those of the

"antient heathen moralists of Tully, of Seneca, of Epictetus [which] would be more full, more

entire, more coherent, and more clearly deduced from unquestionable principles of

knowledge."

Literary Commonplace Book [left page] -

[right page]

Thomas Jefferson, Holograph Manuscript

Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

(61)

|

THE EMERGENCE OF AMERICAN

EVANGELICALISM:

THE GREAT AWAKENING

George Whitefield

George Whitefield

One of the great evangelists of all time, George Whitefield (1714-1770) was ordained in the

Church of England, with which he was constantly at odds. Whitefield became a sensation

throughout England, preaching to huge audiences. In 1738 he made the first of seven visits to

the America, where he gained such popular stature that he was compared to George

Washington. Whitefield's preaching tour of the colonies, from 1739 to 1741,

was the high-water mark of the Great Awakening there. A sermon in Boston

attracted as many as 30,000

people. Whitefield's success has been attributed to his resonant voice, theatrical presentation,

emotional stimulation, message simplification and clever exploitation of emerging advertising

techniques. Some have compared him to modern televangelists.

George Whitefield

Oil on canvas,

attributed to Joseph Badger (1708-1765), c. 1743-65,

Harvard University Portrait Collection,

Gift of Mrs. H.P. (Sarah O.) Oliver

to Harvard College, 1852 (62)

Preaching in the Field

Preaching in the Field

George Whitefield used this collapsible field pulpit for open-air preaching because the doors of

many churches were closed to him. The first recorded use of the pulpit was at Moorsfield,

England, April 9, 1742, where Whitefield preached to a crowd estimated at "twenty or thirty

thousand people." Members of the audience who had come to the park for more frivolous

pursuits showered the evangelist with "stones, rotten eggs and pieces of dead cat" Nothing

daunted, and he won many converts. It is estimated that Whitefield preached two thousand

sermons from his field pulpit.

Portable field pulpit

Oak, c. 1742-1770

American Tract Society,

Garland, Texas (63)

|

Evangelicalism is difficult to date and to define. In 1531, at the beginning of the Reformation,

Sir Thomas More referred to religious adversaries as "Evaungelicalles." Scholars have argued

that, as a self-conscious movement, evangelicalism did not arise until the mid-seventeenth

century, perhaps not until the Great Awakening itself. The fundamental premise of

evangelicalism is the conversion of individuals from a state of sin to a "new birth" through

preaching of the Word.

The first generation of New England Puritans required that church members undergo a

conversion experience that they could describe publicly. Their successors were not as

successful in reaping harvests of redeemed souls. During the first decades of the eighteenth

century in the Connecticut River Valley a series of local "awakenings" began. By the 1730s

they had spread into what was interpreted as a general outpouring of the Spirit that bathed the

American colonies, England, Wales, and Scotland. In mass open-air revivals powerful

preachers like George Whitefield brought thousands of souls to the new birth. The Great

Awakening, which had spent its force in New England by the mid-1740s, split the

Congregational and Presbyterian Churches into supporters--called "New Lights" and "New

Side"--and opponents--the "Old Lights" and "Old Side." Many New England New Lights

became Separate Baptists. Together with New Side Presbyterians (eventually reunited on their

own terms with the Old Side) they carried the Great Awakening into the southern colonies,

igniting a series of the revivals that lasted well into the nineteenth century.

|

Whitefield on the New Birth

Whitefield on the New Birth

The "new birth," prescribed by Christ for Nicodemus (John 3:1-8), was the term

evangelicalism used for the conversion experience. For George Whitefield and other

evangelical preachers the new birth was essential to Christian life, even though, as Whitefield

admitted, "how this glorious Change is wrought in the Soul cannot easily be explained."

The Marks of the New Birth. A Sermon. . .

.

George Whitefield

New York: William Bradford, 1739

Rare Book and Special Collections

Division,

Library of Congress (64)

The Reverend Mr. George Whitefield A.M.

Mezzotint by John Greenwood, after Nathaniel Hone, 1769. Copyprint.

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. (65)

Whitefield Satirized

Whitefield Satirized

George Whitefield acquired many enemies, who assailed evangelicalism as a distortion of the

gospel and attacked him and his followers for alleged moral failings. The evangelist endured

many jibes at his eye disease; hence the epithet "Dr. Squintum." This satire shows an imp

pouring inspiration in Whitefield's ear while a grotesque Fame, listening on the other side

through an ear trumpet, makes accusations on two counts that have dogged revivalists to the

present day: sex and avarice. The Devil, raking in money below the podium, and the caption

raise charges that Whitefield was enriching himself by his ministry. At the lower left,

Whitefield's followers proposition a prostitute, reflecting the line in the caption that "their

Hearts to lewd Whoring extend."

Dr. Squintum's Exaltation or the Reformation

Engraving, London: 1763

Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress

(66)

Whitefield's Death

Whitefield's Death

Whitefield's death and burial at Newburyport, Massachusetts, in 1770 made a deep impression

on Americans from all walks of life. Among the eulogies composed for Whitefield was one

from an unexpected source: a poem by a seventeen-year-old Boston slave, Phillis Wheatley

(ca. 1753-1784), who had only been in the colonies for nine years. Freed by her owners,

Phillis Wheatley continued her literary career and was acclaimed as the "African poetess."

George Whitefield's Burial

Woodcut from Phillis [Wheatley], An Elegiac Poem on the Death

of that celebrated Divine

and eminent Servant of Jesus Christ, the Reverend and learned

George Whitefield

Boston: Ezekiel Russell, 1770

Rare Book and Special Collections Division,

Library of Congress (67)

Jonathan Edwards

Jonathan Edwards

Jonathan Edwards (1703-17) was the most important American preacher during the Great

Awakening. A revival in his church in Northampton, Massachusetts, 1734-1735, was

considered a harbinger of the Awakening which unfolded a few years later. Edwards was

more than an effective evangelical preacher, however. He was the principal intellectual

interpreter of, and apologist for, the Awakening. He wrote analytical descriptions of the

revival, placing it in a larger theological context. Edwards was a world-class theologian,

writing some of the most original and important treatises ever produced by an American. He

died of smallpox in 1758, shortly after becoming president of Princeton.

Jonathan Edwards

White pine tinted with oils, C. Keith Wilbur, M.D., 1982

Courtesy of the artist (68)

The Revival of Northampton

The Revival of Northampton

Jonathan Edwards's( account of a revival in his own church at Northampton, Massachusetts,

and in neighboring churches in the Connecticut Valley was considered a portent of major

spiritual developments throughout the British Empire. Consequently, his Narrative was first

published in London in 1737 with an introduction by two leading English evangelical

ministers, Isaac Watts, the famous hymnist, and John Guyse. In their introduction the two

divines said that "never did we hear or read, since the first Ages of Christianity, any Event of

this Kind so surprising as the present Narrative hath set before us."

A Faithful Narrative of the Surprising Work of God in

the Conversion of Many Hundred Souls

Jonathan Edwards, London: John Oswald, 1737

Rare Book and Special Collections Division,

Library of Congress (69)

Sinners Warned

Sinners Warned

Perhaps Jonathan Edward's only writing familiar to most modern audiences, Sinners in the

Hands of an Angry God was not representative of his vast theological output, which contains

some of the most learned and profound religious works ever written by an American. Like

most evangelical preachers during the Great Awakening, Edwards employed the fear of divine

punishment to bring his audiences to repentance. However, it is a distortion of his and his

colleagues' messages and characters to dismiss them as mere "hellfire" preachers.

Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God

Jonathan Edwards, Boston: 1741

Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

(70)

Trans-Atlantic Evangelicalism

Trans-Atlantic Evangelicalism

The publication by John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, of extracts from Jonathan

Edwards's Distinguishing Marks of a Work of the Spirit of God illustrates the

trans-Atlantic

character of the Great Awakening. The leaders communicated with each other, profited from

each others' publications and were in some cases personal acquaintances.

The Distinguishing Marks of a Work of the Spirit of

God. Extracted from Mr. Edwards

John Wesley, London: William Strahan, 1744

Rare Book and Special Collections Division,

Library of Congress (71)

Gilbert Tennent

Gilbert Tennent

Gilbert Tennent (1703-1764) was the Presbyterian leader of the Great Awakening in the

Middle Colonies. Upon George Whitefield's departure from the colonies in 1741, he

deputized his friend Tennent to come from New Jersey to New England to "blow up the divine

fire lately kindled there." Despite being ridiculed as "an awkward and ridiculous Ape of

Whitefield," Tennent managed to keep the revival going until 1742.

Gilbert Tennent

Oil on canvas, attributed to Gustavus Hesselius (1682-1755)

Princeton University (72)

Criticism of Other Ministers

Criticism of Other Ministers

This famous sermon, which Gilbert Tennent preached at Nottingham, Pennsylvania, in 1740,

was characteristic of the polemics in which both the friends and enemies of the Great

Awakening indulged. Tennent lashed ministerial opponents who had reservations about the

theology of the new birth as "Pharisee-Shepherds" who "with the Craft of Foxes . . . did not

forget to breathe the Cruelty of Wolves in a malicious Aspersing of the Person of Christ."

The Danger of an Unconverted Ministry

Gilbert Tennent, A.M.

Philadelphia: Benjamin Franklin, 1740

Rare Book and Special Collections Division,

Library of Congress (73)

Fundraising for Princeton

Fundraising for Princeton

From the Great Awakening onward, evangelical Christians have founded colleges to train a

ministry to deliver their message. The College of New Jersey (later Princeton University) was

founded in 1746 by New Side Presbyterian sympathizers. This fundraising brochure for the

infant college was prepared in 1764 by the New Side stalwart, Samuel Blair. "Aula

Nassovica," the Latinized version of Nassau Hall, was the principal building of the College of

New Jersey in 1764.

An Account of the College of New Jersey [left

page] -

[right page]

Samuel Blair

Woodbridge, New Jersey: James Parker, 1764

Rare Book and Special Collections Division,

Library of Congress (74)

Samuel Davies

Samuel Davies

Samuel Davies (1723-1761) was the spearhead of the efforts of New Side Presbyterians to

evangelize Virginia and the South. Establishing himself in Hanover County, Virginia, in the

1740s, Davies was so successful in converting members of the Church of England to the new

birth that he was soon embroiled in disputes with local officials about his right to preach the

gospel where he chose.

Samuel Davies

Oil on canvas

Union Theological Seminary and

Presbyterian School of Christian Education, Richmond,

Virginia (75)

Presbyterian Communion Tokens

Presbyterian Communion Tokens

The sacrament of Holy Communion was precious to colonial Presbyterians (and to members of

other Christian churches). Presbyterians followed the Church of Scotland practice of "fencing

the table"--of permitting members to take communion only after being examined by a minister

who vouched for their spiritual soundness by issuing them a token that admitted them to the

celebration of the sacrament. The custom continued in some Presbyterian churches until early

in this century. The tokens shown here were used in the Beersheba Presbyterian Church, near

York, South Carolina.

Presbyterian communion tokens

Metal, c.1800

Courtesy of Martha Hopkins and Nancy Hopkins-Garriss (76)

View on Jones's Falls, Baltimore, Sept. 13,

1818

Engraving and watercolor on paper by J. Hill

Robert C. Merrick Print Collection, Prints and Photographs Department,

Maryland Historical Society Library, Baltimore. (77a)

The Baptists

The Baptists

Although Baptists had existed in the American colonies since the seventeenth century, it was

the Great Awakening that galvanized them into a powerful, proselytizing force. Along with

the Methodists, the Baptists became by the early years of the nineteenth century the principal

Protestant denomination in the southern and western United States. Baptists differed from

other Protestant groups by offering baptism (by immersion) only to those who had undergone a

conversion experience; infants were, therefore, excluded from the sacrament, an issue that

generated enormous controversy with other Christians.

Baptism in Schuylkill River

Woodcut from Morgan Edwards, Materials Towards A History of the American

Baptists.

Copyprint, Philadelphia: 1770

Historical Society of Pennsylvania (77b)

Francis Asbury

Francis Asbury

Methodism, begun by John Wesley and others as a reform movement within the Church of

England, spread to the American colonies in the 1760s. Although handicapped by Wesley's

opposition to the American Revolution, Methodists nevertheless made remarkable progress in

the young American republic. Francis Asbury (1745-1816) was the dynamo who drove the

spectacular growth of the church. He ordained 4,000 ministers, preached 16,000 sermons and

traveled 270,000 miles on horseback, sometimes to the most inaccessible parts of the United

States.

Francis Asbury

Oil on canvas by Charles Peale Polk, 1794

Lovely Lane Museum of United Methodist Historical Society, Baltimore (78)

Beginning of the Methodists

Beginning of the Methodists

The first Methodist meeting in New York City (one of the first in the American colonies) was

held in the sail loft of this Manhattan rigging house in 1766. The five people who attended

helped launch the Methodist Church on a "prosperous voyage" that by 1846, according to the

statistics furnished in the caption, had gathered four million members.

The Rigging House

Color lithograph by A. R. Robinson, 1846

Prints and Photographs Division, Library of

Congress (79)

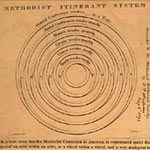

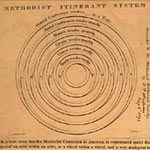

Organization

of the Methodists Organization

of the Methodists

The remarkable growth of the Methodists in the post-Revolutionary period has been attributed

to a hierarchical organizational structure that permitted the maximum mobilization of

resources. The "corporating genius" of the Methodists is depicted in this series of concentric

circles.

Methodist Itinerant System

G. Stebbins and G. King, Broadside

New York: John Totten, 1810-11 [?]

Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

(80)

|

HOME -

EXHIBITION OVERVIEW

HOME -

EXHIBITION OVERVIEW

SECTIONS:

I. America as Refuge -

II. 18th Century America

III. American Revolution -

IV. Congress of the Confederation -

V. State Governments

VI. Federal Government -

VII. New Republic

|

Christ Church, Philadelphia

Christ Church, Philadelphia

A Rural Baptist Church

A Rural Baptist Church Colonial Baptist Church

Colonial Baptist Church Lutheran Church Services

Lutheran Church Services A Deist Tract

A Deist Tract

John Locke

John Locke

Bolingbroke's Influence on Thomas Jefferson

Bolingbroke's Influence on Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson's Literary Commonplace Book

Thomas Jefferson's Literary Commonplace Book George Whitefield

George Whitefield Preaching in the Field

Preaching in the Field Whitefield on the New Birth

Whitefield on the New Birth

Whitefield Satirized

Whitefield Satirized Whitefield's Death

Whitefield's Death Jonathan Edwards

Jonathan Edwards The Revival of Northampton

The Revival of Northampton Sinners Warned

Sinners Warned Trans-Atlantic Evangelicalism

Trans-Atlantic Evangelicalism Gilbert Tennent

Gilbert Tennent Criticism of Other Ministers

Criticism of Other Ministers

Fundraising for Princeton

Fundraising for Princeton Samuel Davies

Samuel Davies Presbyterian Communion Tokens

Presbyterian Communion Tokens

The Baptists

The Baptists Francis Asbury

Francis Asbury Beginning of the Methodists

Beginning of the Methodists Organization

of the Methodists

Organization

of the Methodists