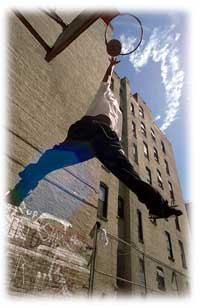

REFLECTIONS: URBAN "HOOP"

By John Edgar Wideman

An Excerpt from Hoop Roots: Basketball, Race and Love

Before John Edgar Wideman became renowned for writing fiction and nonfiction, and for winning two PEN/Faulkner Awards, he was a star basketball player at the University of Pennsylvania. Today, he is Distinguished Professor of English at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. In a recent book, Hoop Roots, Wideman focuses his artistic sensibilities on his inner city background. He compares and contrasts two fundamental passions in his life - writing and playing basketball. When he refers in the excerpt below to the beauty of playing "hoop," he is using a term common on urban playgrounds across America for the game of basketball. Wideman mirrors a long line of American authors who have explored the lessons and meanings of life from the perspective of the playing field or court.

|

The sky's the limit in inner-city |

Growing up, I needed basketball because my family was poor and colored, hemmed in by material circumstances none of us knew how to control, and if I wanted more, a larger, different portion than other poor colored folks in Homewood [an inner city neighborhood of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania], I had to single myself out….

As a kid, did I think about my life in terms of wanting more. More of what. Where would I find it. Did I actually pose similar questions to myself. When. How. Why. Looking back, I'm pretty sure about love, an awakening hunger for the game, and not too sure of much else. The act of looking back, the action of writing down what I think I see/saw, destroys certainty. The past presents itself fluidly, changeably, at least as much a work in progress as the present or future.

No scorebook. No reliable witnesses or too many witnesses. Too much time. No time. One beauty of playground hoop is how relentlessly, scrupulously it encloses and defines moments. Playing the game well requires all your attention. When you're working to stay in the game, the game works to keep you there. None of the mind's subtle, complex operations are shut down when you play, they're just intently harnessed, focused to serve the game's complex demands. In the heat of the game you may conceive of yourself playing the game, an aspect of yourself watching another aspect perform, but the speed of the game, its continuous go and flow, doesn't allow a player to indulge this conscious splitting-off and self-reflection, common, perhaps necessary, to writing autobiography. Whatever advantages such self-division confers are swiftly overridden when you're playing hoop by the compelling necessity to be, to be acutely alert to what you're experiencing as play, the consuming reality of the game's immediate demands. You are the experience. Or it thumps you in the face like a teammate's pass you weren't expecting when you should have been expecting.

Writing autobiography, looking back, trying to recall and represent yourself at some point in the past, you are playing many games simultaneously. There are many selves, many sets of rules jostling for position. None offers the clarifying, cleansing unity of playing hoop. The ball court provides a frame, boundaries, the fun and challenge of call and response that forces you to concentrate your boundless energy within a defined yet seemingly unlimited space. The past is not forgotten when you walk onto the court to play. It lives in the Great Time of the game's flow, incorporating past present and future, time passing as you work to bring to bear all you've ever learned about the game, your educated instincts, conditioned responses, experience accumulated from however many years you've played and watched the game played, a past that's irrelevant baggage unless you can access it instantaneously. Second thoughts useless.

|

Opportunities knock once. And if you think about missing the previous shot when you're attempting the next one, most likely you'll miss it, too. And on and on, you lose, until, unless you get your head back into the game. Into what's next and next and next. The past is crucial, though not in the usual sense. Means everything or nothing depending on how it's employed and how you should employ it strictly, ruthlessly dictated by the flow, the moment. Yes. You can sit back and ponder your performance later, learn from your mistakes, maybe, or spin good stories and shapeshift mistakes into spectacular plays, but none of that's playing ball.

If playground hoop is about the once and only go and flow of time, its unbroken continuity, about time's thick, immersing, perpetual presence, writing foregrounds the alienating disconnect among competing selves, competing, often antagonistic voices within the writer, voices with separate agendas, voices occupying discrete, unbridgeable islands of time and space. Writing, whether it settles into a traditional formulaic set of conventions to govern the relationship between writer and reader or experiments within those borders, relies on some mode of narrative sequencing or "story line" to function as the game's spine of action functions to keep everybody's attention through a linear duration of time. The problem for writers is that story must be invented anew for each narrative. A story interesting to one person may bore another. Writing describes ball games the reader can never be sure anybody has ever played. The only access to them is through the writer's creation. You can't go there or know there, just accept someone's words they exist….

Here's the paradox: hoop frees you to play by putting you into a real cage. Writing cages the writer with the illusion of freedom. Playing ball, you submit for a time to certain narrow arbitrary rules, certain circumscribed choices. But once in, there's no script, no narrative line you must follow. Writing lets you imagine you're outside time, freely generating rules and choices, but as you tell your story you're bound tighter and tighter; word by word, following the script you narrate. No logical reason a playground game can't go on forever. In a sense that's exactly what Great Time, the vast, all-encompassing ocean of nonlinear time, allows the game to do. A piece of writing without the unfolding drama or closure promised or implicit can feel shapeless, like it might go on forever, and probably loses its audience at that point.

Fortunately, graciously, the unpredictability of language, its stubborn self-referentiality, its mysterious capacity to mutate, assert a will of its own no matter how hard you struggle to enslave it, bend it, coerce it to express your bidding, language, with its shadowy, imminent resources and magical emergent properties, sometimes approximates a hoop games freedom. The writer feels what it's like to be a player when the medium rules, when its constraints are also a free ride to unforeseen, unexpected, surprising destinations, to breaks and zones offering the chance to do something, be somebody, somewhere, somehow new….

Given all the above, I still want more from writing…. Not because I expect more from writing, I just need more. Want to share the immediate excitement of process, of invention, of play. (Maybe that's why I teach writing.) Need more in the same way I needed more as I was growing up in Homewood. Let me be clear. The more I'm talking about then and now is not simply an extra slice of pie or cake. Seeking more means self-discovery. Means redefining the art I practice. In the present instance, wanting to compose and share a piece of writing that won't fail because it might not fit someone else's notion of what a book should be….

We're plagued, even when we have every reason to know better, by deep-seated anxieties - are we doomed because we are not these "white" other people, are we fated, because we are who we are, never to be good enough. I need writing because it can extend the measure of what's possible, allow me to engage in defining standards. In my chosen field I can strive to accomplish what [former U.S. professional basketball star] Michael Jordan has achieved in playing hoop - become a standard for others to measure themselves against.

So playground basketball and writing, alike and unlike, both start there - ways to single myself out. Seeking qualities in myself worth saving, something others might appreciate and reward, qualities, above all, I can count on to prove a point to myself, to change myself for better or worse. Hoop and writing intrigue me because no matter how many answers I articulate, how gaudy my stat [statistics] sheet appears, hoop and writing keep asking the same questions. Is anybody home in there. Who. If I take a chance and turn the sucker out, will he be worth … the trouble. Or shame me. Embarrass me. Or represent. Shine forth.

|

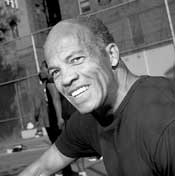

(Jean-Christian Bourcart) |

John Edgar Wideman is the author of Sent For You Yesterday and Philadelphia Fire, among other novels, and several volumes of nonfiction, including a memoir, Brothers and Keepers, and Fatheralong: A Meditation on Fathers and Sons, Race and Society.

Excerpted from Hoop Roots, by John Edgar Wideman. Copyright © 2001 by John Edgar Wideman. Used by permission of Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.