REFLECTIONS: WHY WE PLAY THE GAME

By Roger Rosenblatt

"The first time a baseball is hit, the first time a football is thrown with a spiral, the first time a boy or a girl gains the strength to push the basketball high enough into the hoop – these are national rites of passage."

|

Professional basketball star Swin Cash, of the Women's National Basketball Association team, the Detroit Shock, shoots and scores. |

There probably are countries where the people are as crazy about sports as they are in America, but I doubt that there is any place where the meaning and design of the country is so evident in its games. In many odd ways, America is its sports. The free market is an analog of on-the-field competition, apparently wild and woolly yet contained by rules, dependent on the individual's initiative within a corporate (team) structure, at once open and governed. There are no ministries of sports, as in other countries; every game is a free enterprise partially aided by government, but basically an independent entity that contributes to the national scene like any big business. The fields of play themselves simulate the wide-open spaces that eventually ran out of wide-open spaces, and so the fences came up. Now every baseball diamond, football field and basketball court is a version of the frontier, with spectators added, and every indoor domed stadium, a high-tech reminder of a time of life and dreams when the sky was the limit.

I focus on the three sports of baseball, football, and basketball because they are indigenous to us, invented in America (whatever vague debt baseball may owe the British cricket), and central to the country's enthusiasms. Golf and tennis have their moments; track and field as well. Boxing has fewer and fewer things to cheer about these days, yet even in its heyday, it was less an American sport than a darkly entertaining exercise in universal brutality. But baseball, football, and basketball are ours - derived in unspoken ways from our ambitions and inclinations, reflective of our achievement and our losses, and our souls. They are as good and as bad as we are, and we watch them, consciously or not, as morality plays about our conflicting natures, about the best and worst of us. At heart they are our romances, our brief retrievals of national innocence. Yesterday's old score is tomorrow's illusion of rebirth. When a game is over, we are elated or defeated, and we reluctantly re-enter our less heightened lives, yet always driven by hope, waiting for the next game or for next year.

But from the beginning of a game to its end, America can see itself played out by representatives in cleats or shorts or shoulder pads. Not that such fancy thoughts occur during the action. Part of being an American is to live without too much introspection. It is in the undercurrents of the sports that one feels America, which may be why the attraction of sports is both clear-cut (you win or you lose) and mysterious (you win and you lose).

Of the three principal games, baseball is both the most elegantly designed and the easiest to account for in terms of its appeal. It is a game played within strict borders, and of strict dimensions - a distance so many feet from here to there, a pitcher's mound so many inches high, the weight of the ball, the weight of the bat, the poles that determine in or out, what counts and does not, and so forth. The rules are unbending; indeed, with a very few exceptions, the game's rules have not changed in a hundred years. This is because, unlike basketball, baseball does not depend on the size of the players, but rather on a view of human evolution that says that people do not change that much - certainly not in a hundred years - and therefore they should do what they can within the limits they are given. As the poet Richard Wilbur wrote: "The strength of the genie comes from being in a bottle."

|

Baseball is a sport of the individual. |

And still, functioning within its limits, first and last, baseball is about the individual. In other sports, the ball does the scoring. In baseball, the person scores. The game was designed to center on Americans in our individual strivings. The runner on first base has a notion to steal second. The first baseman has a notion to slip behind him. The pitcher has a notion to pick him off, but he delivers to the plate where the batter swings to protect the runner who decides to go now, and the second baseman braces himself to make the tag if only the catcher can rise to the occasion and put a low, hard peg on the inside of the bag. One doesn't need to know what these things mean to recognize that they all test everyone's ability to do a specific job, to make a personal decision, and to improvise.

Fans cling to the glory moments of the game's history, especially the heroic names and heroic deeds (records and statistics). America holds dear all its sports heroes because the country does not have the long histories of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Lacking an Alexander the Great or a Charlemagne, it draws its heroic mythology from sports.

|

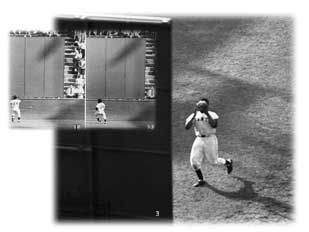

One of the great defensive plays in baseball history was New York Giants centerfielder Willie Mays' over-the-shoulder catch of a fly ball in the deep outfield of the Polo Grounds in the 1954 World Series. |

We also cherish the game's sublime moments because such memories preserve everybody's youth as part of America's continuing, if a bit strained, need to remain in a perpetual summer. The illusion of the game is that it will go on forever. (Baseball is the only sport in which a team, down by a huge deficit, with but one hitter left, can still win.) In the 1950s, one of the game's greatest players, Willie Mays of the New York Giants, made a legendary catch of a ball hit to the deepest part of one of the largest stadiums, going away from home plate, over his shoulder. It was not only that Willie turned his back and took off, it was the green continent of grass on which he ran and the waiting to see if he would catch up with the ball and the reek of your sweat and of everyone else's who sat like Seurat's pointillist dots in the stadium, in the carved-out bowl of a planet that shines pale in daylight, bright purple and emerald at night.

|

American football is marked by progress |

The game always comes back to the fundamental confrontation of pitcher and batter, with the catcher involved as the only player who faces the field and sees the whole game; he presides as a masked god squatting. The pitcher's role is slyer than the batter's, but the batter's is more human. The pitcher plays offense and defense simultaneously. He labors to tempt and to deceive. The batter cannot know what is coming. He can go down swinging or looking at a strike and be made to appear the fool. Yet he has a bat in his hands. And if all goes well and he can accomplish that most difficult feat in sports by hitting a small, hard sphere traveling at over ninety miles per hour with a heavy rounded stick, well then, fate is thwarted for a moment and the power over life is his. The question ought not to be, "Why do the greatest hitters connect successfully only a third of the time?" It ought to be, "How do they get a hit at all?"

Still, the youth and hope of the game constitute but one half of baseball, and thus one half of its meaning to us. It is the second summer of the baseball season that reveals the game's complete nature. The second summer does not have the blithe optimism of the first half of the season. Each year, from August to the World Series in October, a sense of mortality begins to lower over the game - a suspicion that will deepen by late September to a certain knowledge that something that was bright, lusty, and overflowing with possibility can come to an end.

The beauty of the game is that it traces the arc of American life, of American innocence eliding into experience. Until mid-August, baseball is a boy in shorts whooping it up on the fat grass, afterwards it becomes a leery veteran with a sun-baked neck, whose main concern is to protect the plate. In its second summer, baseball is about fouling off death. Sadaharu Oh, the Babe Ruth of Japanese baseball, wrote an ode to his sport in which he praised the warmth of the sun and foresaw the approaching change to "the light of winter coming."

Small wonder that baseball produces more fine literature than any other sport. American writers - novelists Ernest Hemingway, John Updike, Bernard Malamud, and poet Marianne Moore - have seen the nation of dreams in the game. The country's violation of its dreams lies here too. Like America itself, baseball fought against integration until Jackie Robinson, the first Major League African American, stood up for all that the country wanted to believe. America, too, resisted its own self-proclaimed destiny to be the country of all the people and then, when it did strive to become the country of all the people - black, Asian, Latino, everyone - the place improved. Baseball also improved.

On mute display in baseball is the design of the U.S. Constitution itself. The basic text of the Constitution is the main building, a symmetrical 18th-century structure grounded in the Enlightenment's principles of reason, optimism, order, and a wariness of emotion and passion. The Constitution's architects, all fundamentally British Enlightenment minds, sought to build a house that Americans could live in without toppling it by placing their impulses above their rationality. But the trouble with that original body of laws was that it was too stable, too rigid. Thus, the Founders came up with the Bill of Rights, which in baseball's terms may be seen as the encouragement of individual freedom within hard and fast laws. Baseball is at once classic and romantic. So is America. And both the country and the sport survive by keeping the two impulses in balance.

If baseball represents nearly all the country's qualities in equilibrium, football and basketball show where those qualities may be exaggerated, overemphasized, and frequently distorted. Football and basketball are not beautifully made sports. They are more chaotic, more subject to wild moments. And yet, it should be noted that both are far more popular than baseball, which may suggest that Americans, having established the rules, are always straining to break them.

Football, like baseball, is a game of individual progress within borders. But unlike baseball, individual progress is gained inch by inch, down and dirty. Pain is involved. The individual fullback or halfback who carries the ball endures hit after hit as he moves forward, perhaps no more than a foot at a time. Often he is pushed back. Ten yards seems a short distance yet, as in a war, it often means victory or defeat.

|

For American kids, the games start early. |

The ground game is operated by the infantry; the throwing game by the air force. Or one may see the game in the air as the function of the "officers" of the team - those who throw and catch - as opposed to the dog-faced linesmen in the trenches, those literally on the line. These analogies to war are hardly a stretch. The spirit of the game, the terminology, the uniforms themselves, capped by protective masks and helmets, invoke military operations. Injuries (casualties) are not exceptions in this sport; they are part of the game.

And yet football reflects our conflicting attitudes toward war. Generally, Americans are extremely reluctant to get into a war, even when our leaders are not. We simply want to win and get out as soon as possible. At the start of World War II, America ranked 27th in armaments among the nations of the world. By the war's end, we were number one, with second place nowhere in sight. But we only got in to crush gangsters and get it over with. Thus, football is war in its ideal state, war in a box. It lasts four periods. A fifth may be added because of a tie, and ended in "sudden death." But unless something freakish occurs, no warrior really dies.

Not only do the players resemble warriors; the fans go dark with fury. American football fans may not be as lethal as European football (soccer) fans, yet every Sunday fans dress up like ancient Celtic warriors with painted faces and half-naked bodies in midwinter.

Here is no sport for the upper classes. Football was only that in the Ivy League colleges of the 1920s and 1930s. Now, the professional game belongs largely to the working class. It makes a statement for the American who works with his hands, who gains his yardage with great difficulty and at great cost. The game is not without its niceties; it took a sense of invention to come up with a ball whose shape enables it to be both kicked and thrown. But basically this is a game of grunts and bone breakage and battle plans (huddles) that can go wrong. It even has the lack of clarity of war. A play occurs, but it is not official until the referee says so. Flags indicating penalties come late, a play may be nullified, called back, and all the excitement of apparent triumph can be deflated by an exterior judgment, from a different perspective.

Where football shows America essentially, though, is the role of the quarterback. My son Carl, a former sports writer for The Washington Post, pointed out to me that unlike any other sport, football depends almost wholly on the ability of a single individual. In other team sports, the absence of a star may be compensated for, but in football the quarterback is everything. He is the American leader, the hero, the general, who cannot be replaced by teamwork. He speaks for individual initiative, and individual authority. And just as the president - the Chief Executive of the land - has more power than those in the other branches of government that are supposed to keep him in check, so the quarterback is the president of the game. Fans worship or deride him with the same emotional energy they give to U.S. presidents.

As for the quarterback himself, he has to be what the American individual must be to succeed - both imaginative and stable - and he must know when to be which. If the plays he orchestrates are too wild, too frequently improvised, he fails. If they are too predictable, he fails. All the nuances of American individualism fall on his shoulders and he both demonstrates and tests the system in which the individual entrepreneur counts for everything and too much.

The structure of basketball, the least well-made game of our three, depends almost entirely on the size of the players, therefore on the individual. Over the years, the dimensions of the court have changed because players were getting bigger and taller; lines were changed; rules about dunking the ball changed, and changed back for the same reason. Time periods are different for professionals and collegians, as is the time allowed in which a shot must be taken. Some other rules are different as well. The game of basketball begins and ends with the individual and with human virtuosity. Thus, in a way, it is the most dramatically American sport in its emphasis on freedom.

Integration took far less time in basketball than in the other two major American sports because early on it became the inner city game, and very popular among African Americans. But the pleasure in watching a basketball game derives from the qualities of sport removed from questions of race. Here is a context where literal upward mobility is demonstrated in open competition. Black or white, the best players make the best passes, block the most shots, score the most points.

Simulating other American structures, both corporate and governmental, the game also demonstrates how delicate is the balance between individual and team play. Extraordinary players of the past such as Oscar Robertson, Walt Frazier, and Bill Russell showed that the essence of basketball was teamwork; victory required looking for the player in the best position for a shot, and getting the ball to him. A winning team was a selfless team. In recent years, most professional teams have abandoned that idea in favor of the exceptional talents of an individual, who is sometimes a showboat. Yet it has been proved more often than not that if the individual leaves the rest of the team behind, everybody loses.

|

The deep appeal of basketball in America lies in the fact that the poorest of kids can make it rich, and that there is a mystery in how he does it. Neither baseball nor football creates the special, jazzed-up excitement of this game in which the human body can be made to do unearthly things, to defy gravity gracefully. A trust in mystery is part of the foolishly beautiful side of the American dream, which actually believes that the impossible is possible.

This belief goes to the heart of sports in America. It begins early in one's life with a game of catch, or tossing a football around, or kids shooting basketballs in a playground. The first time a baseball is hit, the first time a football is thrown with a spiral, the first time a boy or a girl gains the strength to push the basketball high enough into the hoop - these are national rites of passage. In a way, they indicate how one becomes an American whether one was born here or not.

Of course, what is a grand illusion may also be spoiled. The business of sports may detract from its sense of play. The conflicts between rapacious owners and rapacious players may leave fans in the lurch. The fans themselves may behave so monstrously as to poison the game. Professionalism has so dominated organized sports in schools that children are jaded in their views of the games by the time they reach high school. Like sports, America was conceived within a fantasy of human perfection. When that fantasy collides with the realities of human limitations, the disappointment can be embittering.

Still, the fantasy remains - of sports and of nations. America only succeeds in the world, and with itself, when it approaches its own stated ambitions, when it yearns to achieve its purest form. The same is true of its sports. Both enterprises center on an individual rising to the top and raising others up with him, toward a higher equality and a victory for everybody. This is why we play the games.

|

(Mario Ruiz/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images) |

Roger Rosenblatt is a journalist, author, playwright, and professor. As an essayist for Time magazine, he has won numerous print journalism honors, including two George Polk Awards, as well as awards from the Overseas Press Club and the American Bar Association. The essays he presents on the public television network in the United States have gained him the prestigious Peabody and Emmy awards. He is the author, most recently, of Where We Stand: 30 Reasons for Loving Our Country, and Rules for Aging: A Wry and Witty Guide to Life.