GAMES FOR THE WHOLE WORLD

By David Goldiner

Baseball and basketball, and to a lesser extent American football, have captured the imagination of athletes and sports fans around the world. In the U.S. professional and university leagues, foreign-born players are increasingly making their marks in those games as well as in ice hockey, soccer, and other sports.

|

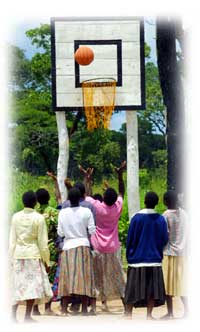

Congolese girls shoot hoops |

On a dusty basketball court outside Johannesburg, South Africa, this past September, Michel Los Santos, a 17-year-old boy from Angola, drilled one long-range shot after another into the basket. Powerfully built Nigerian center Kenechukwu Obi, 15, huffing and puffing after grabbing a rebound, admitted he had touched a basketball for the first time only three months earlier. Rail-thin Cheikh Ahmadou Bemba Fall said most of his friends in the Senagalese port city of St. Louis play basketball in bare feet.

The three players were among 100 young African talents who gathered at the U.S. National Basketball Association's (NBA) first-ever professional development camp on the continent.

All-Star center Dikembe Mutombo, who himself was plucked from obscurity in Zaire 15 years ago, tutored the youngsters with some basic moves – and offered invaluable words of encouragement. "I want them to know that they can make it to another level if you want to push yourself," said Mutombo, who frequently visits his homeland, which is now called the Democratic Republic of Congo.

"The NBA is becoming a global game," said Mutombo, who now plays for the NBA's New York Knicks team. "In the past, soccer would be most popular, but today, in any country, young kids will recognize, in two seconds, 10 NBA players. The league should be proud of that success."

Armed with visions of fame and million-dollar contracts to play ball in the United States, the 100 players came from poverty-stricken townships of South Africa, crowded cities of Nigeria, and the edge of the Sahara Desert.

Will any of them ever see their dreams fulfilled? Maybe not. But their very presence at the camp, not to mention the stands packed with sports agents and scouts, demonstrates the growing global reach of American sports. Basketball, baseball, American football, and ice hockey are now multi-billion dollar industries that promote themselves – and recruit new talent – in the four corners of the world.

A Two-Way Street

The phenomenon is an unusual cultural two-way street: American sports are beamed around the world by omnipresent TV and Internet connections. In return, foreign stars have flooded onto the fields, courts, and rinks of the U.S. pro leagues and major colleges in recent years like never before.

Jaromir Jagr, the high-scoring wing for the Washington Capitals hockey team, has led a veritable invasion of talented players from East Europe and the former Soviet Union. In baseball, slugger Sammy Sosa is just one of dozens of stars from the Dominican Republic to make their mark on Major League Baseball. Japanese stars like Ichiro Suzuki and Koreans like Chan Ho Park have boosted the sport's popularity in the Pacific Rim.

Chinese basketball center Yao Ming, high-scoring forward Dirk Nowitzki from Germany, and Brazilian Nene Hilario have emerged from little-known basketball backwaters to star in the NBA. Female track stars have made their mark in college athletics and female basketball stars – buoyed by the popularity of women's basketball in countries like Portugal and Brazil – have internationalized the new Women's National Basketball Association, or WNBA.

"It's now a game for the whole world," said Serbian-born center Vlade Divac, who plays for the Sacramento Kings.

For The Love Of The Game

It wasn't always that way. American scouts and trainers were once lonely altruists helping athletes in developing countries for the love of the game.

|

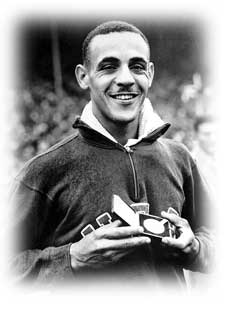

Mal Whitfield was one of America's |

Track star Mal Whitfield won three Olympic gold medals in the 1948 and 1952 Games. With the Cold War raging, the U.S. government decided to send world-class American athletes on goodwill missions around the world and picked Whitfield to be one of the first such ambassadors.

Whitfield, now 79 and retired, spent much of the next four decades traveling the globe and training young track stars. He even lived in countries like Kenya, Uganda, and Egypt under the then U.S. Information Agency's Sports America program. The result was a harvest of good will for America – and a bounty of Olympic medals for African athletes. He trained legends like distance runner Kip Keino of Kenya, who took home two gold medals, and hurdler John Akii-Bua of Uganda, who won a gold in 1972.

Whitfield also inspired a second wave of American coaches to teach in – and learn from – Africa, including Ron Davis, who became a national track coach in Tanzania, Mozambique, and Mauritius.

"I know the meaning of sports," Whitfield said in a 1996 interview. "All Americans have a job to do. I just happen to be one proud American."

The successes, in addition to producing a wave of medals for Olympic athletes, triggered an influx of athletes from developing nations to American universities, which typically set aside a set number of scholarships for a variety of sports, even some less popular ones such as wrestling, fencing, and track. But the exposure failed to dent America's major professional sports leagues, which were overwhelmingly dominated by U.S.-born athletes.

The Charisma Of One Player

About two decades ago, the picture started to change. Foreign audiences started tuning into American pro sports, especially basketball, in previously unheard of numbers. Teenagers snapped up player jerseys and stayed up past midnight to watch games on live television. Soon, they were imitating the moves on their own courts and fields.

So What Happened? In Two Words: Michael Jordan

More than any single athlete, Jordan, the magnetic and charismatic Chicago Bulls superstar, transformed American sports into a global phenomenon. Jordan's soaring dunks and graceful athleticism made him a worldwide poster child for the American dream. Starting in the late 1980s, he drew hundreds of millions of dollars into the sport and became one of the most recognized persons in the world.

|

"Michael made it matter all over the world," Indianapolis Star columnist Bob Kravitz wrote in an article celebrating Jordan's retirement last season.

Of course, American stars have long been global cultural icons. In music, Michael Jackson and Madonna sold millions of albums worldwide. Actors like Eddie Murphy and Richard Gere became household names from Delhi to Dakar. But the massive exposure of American sports did more than just sell jerseys - it brought a powerful new pool of talent to the game.

One day in 1995, a tall kid named Maybyner (Nene) Hilario watched an NBA game on TV in his family's cramped home outside the industrial city of Sao Carlos, Brazil. The next day he skipped his usual soccer game and played a pickup game on a makeshift court created from a basket mounted on a battered car in an empty lot. Hilario, now 21, dunked the ball with such force, he brought down the hoop. Now, he is playing for the Denver Nuggets.

Half a world away, Mwadi Mabika would sit for hours watching boys play basketball on a dirt court in front of her family's home in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo. The boys would taunt the eight-year-old girl, telling her she could shoot the ball for five minutes if she swept sand off the court.

"So I would clean it, but sometimes they wouldn't give me the ball," said Mwadi, now a star with the WNBA's Los Angeles Sparks.

In a smoke-filled gymnasium in the Serbian town of Vrsac, a bony 14-year-old named Darko Milicic was practicing with a new team that lured him with a $100-a-month salary. Suddenly, air raid sirens ripped through the air and explosions rang out as NATO warplanes launched the bombing campaign to force Serbia out of the restive province of Kosovo. The frightened players stopped in their tracks and peered over at their coach, who shouted at them to keep playing.

The results of stories like these are written indelibly on the rosters of pro teams. In 1990, 20 foreign-born players played in the NBA. Last season there were 68.

American Football in Europe

American football has also seen an international boom, albeit on a smaller scale. For years, the National Football League (NFL) had recruited soccer-playing foreigners as kickers, including legends like Morten Anderson of Denmark, South African Gary Anderson, and Portugal-born Olindo Mare. But non-U.S. players remained rare in a sport that was largely unknown outside of North America.

The international profile of American football got a boost from the launch of the NFL Europe league, which provides an opportunity for some European neophytes to play against somewhat lesser American professional talents. Many of the foreigners – 90 made preseason rosters in the NFL this season – are sons of immigrants from places like Mexico or West Africa.

|

Adewale Ogunleye's parents, natives of Nigeria, tried to steer him away from football, with its hard hitting, and its helmets and pads. "They thought it was barbaric," he said recently. But growing up in New York City, he stuck with the sport and now is a star defensive lineman for the Miami Dolphins.

Antonio Rodriguez, who is trying to land a spot with the Houston Texans team, said his Mexican friends didn't believe him when he told them he was playing football in college. "They thought . . . I meant soccer," said Rodriguez.

For ice hockey, the biggest barrier to playing in the United States was always political. The sport had the advantage of already being hugely popular in countries across northern and eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. But for decades, Communist governments prevented star players from leaving their countries or signing pro contracts.

"They didn't allow people to think freely or do whatever they wanted," said former Soviet Olympic hero Vyacheslav Fetisov. "They wanted the control of the people. . . . It was scary."

All that changed as the Iron Curtain started to collapse in the late 80s, setting off a stampede of players from Russia. Fetisov, the first to leave, went on to win two Stanley Cups with the Detroit Red Wings. He was followed by flashy scorer, Pavel Bure, and puck-handler Sergei Zubov, who grew up playing hockey on the frozen ponds of Moscow.

"I knew about NHL (National Hockey League), but I never had any thought to play there," Zubov said. "We didn't think that way." Now, more than 60 players from the former Soviet Union play in the NHL.

The Russians were followed by Jagr, who grew up milking cows on a farm in the Czech Republic and chose the number 68 to honor his country's resistance during the Soviet invasion of 1968. Jagr says his number "is about history, in Czech."

The Latin Americanization Of Baseball

American baseball didn't have to look across the Atlantic for a vast pool of new talent. It was right there for anyone to see in the sugar cane fields and hardscrabble city lots of Latin American countries like Venezuela, Panama, and, especially, the Dominican Republic.

For decades, a trickle of Latin players – Mexican pitcher Fernando Valenzuela and Dominican curveball wizard Juan Marichal – gave baseball fans a taste of the panache and talent that lay south of the border. In the past decade, the tap has opened up and now more than a quarter of all Major League Baseball players were born outside the United States.

It didn't take TV exposure or the Internet to show young Dominicans like slugger Sammy Sosa or pitcher Pedro Martinez how to play ball. Beisbol has been the island's favorite game ever since it was brought to its shores more than a century ago.

Sosa grew up selling oranges and shining shoes on the streets of San Pedro de Macoris, a baseball-mad port city outside the capital of Santo Domingo. His neck-and-neck battle with Mark McGwire to break the single season homerun record in 1998 – won by McGwire – opened even more eyes to the limitless untapped talent in the Dominican Republic. Today, virtually every major league team has its own training academy on the island and others are scouring Panama, Venezuela, and Central America for new stars.

Cuba, with some of the best talent anywhere, could prove to be an even richer pool of talent, but Fidel Castro's Communist government still does its best to keep stars from leaving. The far East is also a potent new market, as evidenced by the Japanese and even Korean stars trooping to the United States to prove their mettle.

All the statistics and long-term trends meant little to Los Santos, the Angolan teenager who showed off his stuff at the NBA camp in South Africa. On a continent where sneakers and balls are a luxury, Los Santos counts himself lucky to play in a league with coaches and paved courts in the war-ravaged capital of Luanda. Like millions of kids around the world, he sees his talent as a long-shot ticket to rags-to-riches success in America.

"I want to go to college," Los Santos said, flashing a smile. "Then I want money and fame."

David Goldiner is a writer and reporter for the New York Daily News.