Map Locating Noblesville, Indiana |

Landownership maps and atlases were published by commercial

companies, usually on a subscription basis, for the wealthier

rural areas. Landownership atlases also documented the migration

of blacks to the Midwest. A map of Noblesville, the fifth seat

of Hamilton, County, Indiana, shows the site of the Roberts

Settlement. In 1909, Stephen Roberts Jr. (b. 1849), grandson of

Willis Roberts, the first settler, was still buying cattle in

Noblesville.

Hamilton County, Indiana

Indiana: The Hamilton Trust Company, 1906

Map

Geography and Map Division (98)

|

Roberts Settlement Land Grant |

Abraham Jones's 1837 land-grant certificate, signed by President

Martin Van Buren, is typical of those issued to the colonists of

the Roberts Settlement.

Land grant certificate

The Roberts Family Papers, 1734-1944

Manuscript Division (99)

|

Roberts Family Genealogical Chart |

The Roberts family chart traces the descendants of James Roberts

I of Northampton County, North Carolina, grandfather of Willis

Roberts (1782-1846) and founder of the Roberts Settlement in

Noblesville, Indiana. Willis Roberts became a prosperous farmer

and eventually married Mary Marthaline Hunt. They had eight

children born between 1803 and 1819.

Photocopy of manuscript chart

Roberts Family Papers, 1734-1944

Manuscript Division (100)

|

Jobs of Black Women in World War I |

During World War I, industrial opportunities became available to

women when workers were needed to replace men drafted into

military service. Black women responded to the demand by leaving

their homes and domestic jobs. This chart shows a sampling of

the industrial occupations of 21,547 black women in approximately

seventy-five specific processes, at 152 plants, during the period

December 1, 1918, to June 30, 1919. The report was made by Mrs.

Helen B. Irvin, Special Agent of the Women's Bureau on 1918-1919.

United States. Department of Labor. Division of Negro Economics.

The Negro at Work During the World War and During Reconstruction:

Statistics, Problems, and Policies Relating to the Greater

Inclusion of Negro Wage Earners in American Industry and

Agriculture, p. 125

New York: Negro Universities Press, 1969

General Collections (101)

|

Founder and Editor of the Chicago Defender |

African-American journalist Robert Sengstacke Abbott (1868-1940)

founded the Chicago Defender on May 6, 1905, with a capital

totalling twenty-five cents. His editorial creed was to fight

against "segregation, discrimination, disenfranchisement . . . ."

The Defender reached national prominence during the mass

migration of blacks from the South during World War I, when the

paper's banner headline for January 6, 1917, read "Millions to

Leave South." The Defender became the bible of many seeking "The

Promised Land." Abbott advertised Chicago so effectively that

even migrants heading for other northern cities sought

information and assistance from the pages of the "Worlds Greatest

Weekly."

Kenneth L. Kusmer, Ed.

The Great Migration and After, 1917-1930, vol. 5, p. 4

Black Communities and Urban Development in America, 1720-1990,

vol. 5

New York: Garland, 1991

General Collections (102)

|

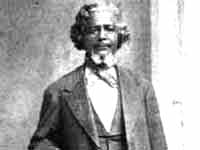

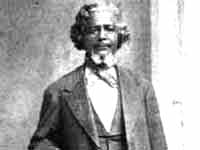

The "Exoduster" Movement |

Benjamin "Pap" Singleton (1809-1892), a former slave born in

Nashville, Tennessee, became the leader of the "Exoduster

Movement" of 1879, and in later years he was accorded the title

"Father of the Exodus." In the late 1860s, Singleton and his

associates urged blacks to acquire farmland in Tennessee, but

whites would not sell productive land to them. As an alternative

Singleton began scouting land in Kansas in the early 1870s. Soon

several black families migrated from Nashville. By 1874,

Singleton and his associates had formed the Edgefield Real Estate

and Homestead Association in Tennessee, which steered more than

20,000 black migrants to Kansas between 1877 and 1879. In 1880

Singleton claimed to be "the whole cause of the Kansas

immigration," in testimony before a U.S. committee on the "exodus

to Kansas."

Nell Irvin Painter

Exodusters: Black Migration to Kansas After the Reconstruction,

p. 100

New York: Knopf, 1977

General Collections (103)

|

Emigrants Travelling to Kansas |

In February of 1880, more than 900 black families from

Mississippi reached St. Louis, en route to Kansas. Some black

migrants sought "conductors" to make travel arrangements for

them. These conductors would often ask for money in advance and

not show up at the appointed departure time, leaving migrants

stranded at docks and train stations.

Refugees on Levee, 1897. Carroll's Art Gallery. Photomural from gelatin-silver print Prints and Photographs Division (105)

Prints and Photographs Division (105)

|

Exodusters En Route To Kansas |

At the time of the Exodus to Kansas, yellow fever ravaged many

river towns in Missouri, Mississippi, and Louisiana. Because

many of the black migrants who stopped over in these towns --

coming by steamboat, train, or horseback -- were sick, unwashed,

and poverty-stricken, it was assumed by city officials that they

must be potential disease carriers. This caused great alarm in

such cities as St. Louis, which imposed unnecessary quarantine

measures to discourage future migrants.

"Negro Exodusters en route to Kansas, fleeing from the yellow fever, " Photomural from engraving. Harpers Weekly, 1870. Historic American Building Survey Field Records, HABS FN-6, #KS -49-11

Prints and Photographs Division (106)

|

Exoduster Leaders |

In 1874 Benjamin Singleton and his associates formed the

Edgefield Real Estate and Homestead Association in Tennessee.

This association sought out the best locations for black

settlements. Singleton tried to establish a well-planned and

organized movement to Kansas, but by 1879, the unruly, mass

Exodus had overwhelmed his efforts.

Benjamin Singleton, and S.A. McClure, Leaders of the Exodus, leaving Nashville, Tennessee.

Photomural from montage. Historic American Building Survey Field Records,

HABS FN-6, #KS-49-12

Prints and Photographs Division (107)

|

Advertisement for Kansas |

Blacks had obtained information about Kansas by several means:

letters from migrants, who settled in Nicodemus and other

locations; circulars; and mass meetings. Benjamin Singleton

printed handbills in an attempt to attract blacks to visit or

settle in Kansas. One such flier was headed: "Ho For Kansas!"

"Ho For Kansas!" Copyprint of handbill. Historic American Building Survey Field Records, HABS FN-6, #KS-49-14

Prints and Photographs Division (109) |

![[Previous]](prev.gif)

![[Next]](next.gif)

Library of Congress

Library of Congress