Robert E. Lee's Former Slaves Go to Liberia

|

Before the Civil War, Robert E. Lee freed most of his slaves

and offered to pay expenses for those who wanted to go to Liberia. In November

1853, Lee's former slaves William and Rosabella Burke and their four children

sailed on the Banshee, which left Baltimore with 261 emigrants.

A person of superior intelligence and drive, Burke studied Latin and Greek

at a newly established seminary in Monrovia and became a Presbyterian minister

in 1857. He helped educate his own children and other members of his community

and took several native children into his home. The Burkes's letters describing

their lives in Liberia show that they relied on the Lees to convey messages

to and from relatives still in Virginia, and the letters also reflect affection

for their former masters.

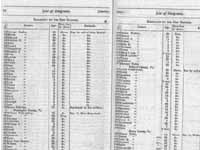

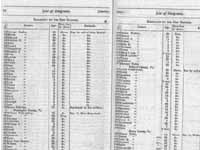

"Table of Emigrants," in The African Repository and Colonial Journal,

vol. 30, no. 1, January 1854, p. 121 Journal General

Collections (17)

|

Letter from Liberian Colonist William Burke

|

Despite the hardships of being a colonist, William Burke was

enthusiastic about his new life. After five years in Liberia he wrote that

"Persons coming to Africa should expect to go through many hardships, such

as are common to the first settlement in any new country. I expected it,

and was not disappointed or discouraged at any thing I met with; and so

far from being dissatisfied with the country, I bless the Lord that ever

my lot was cast in this part of the earth. The Lord has blessed me abundantly

since my residence in Africa, for which I feel that I can never be sufficiently

thankful."

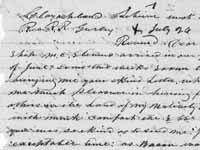

[Letter from William Burke to ACS president Ralph R. Gurley], July 26,

1858 American Colonization Society Papers Manuscript

Division (18)

|

Letter from Liberian Colonist Rosabella Burke

|

Letters from the Burkes to Mary Custis Lee, wife of Robert

E. Lee, were published in the 1859 edition of The African Repository

with Mrs. Lee's permission. This letter from Mrs. Burke to Mrs. Lee demonstrates

personal warmth between the two women. Mrs. Burke shows concern for Mrs.

Lee's health, tells Mrs. Lee about her children, and asks about the Lee

children. The "little Martha" referred to was Martha Custis Lee Burke, born

in Liberia and named for one of the Lee family. Repeating her husband's

enthusiasm for their new life, Rosabella Burke says, "I love Africa and

would not exhange it for America."

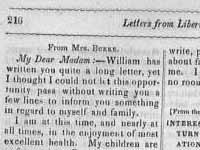

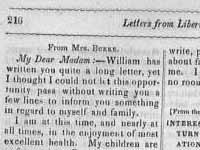

[Letter from Rosabella Burke to Mary Custis Lee], February 20, 1859,

in The African Repository and Colonial Journal, vol. 35,

no 7, July 1859, p. 216 General

Collections (20)

|

Information on Emigrants to Liberia

|

The ACS required potential emigrants to complete a form as

part of their application for settlement in Liberia. This example lists

twelve slaves whose master, Timothy Rogers of Bedford County, Virginia,

freed them in his will under the condition that they go to Liberia. A note

reveals that one of the group preferred to remain a slave if he were unable

to free his wife, the property of another owner, to go with him. Forms like

this provide a wealth of demographic and genealogical information about

emigrants to Liberia.

"Applicants for Passage to Liberia," ca. 1852 American Colonization

Society Papers Manuscript Division

(21)

|

St. Paul's River Landscape

|

Because the soil around Monrovia was poor and the coastal

areas were covered in dense jungle, many early emigrants to Liberia moved

up the nearby St. Paul's River, where they found land suitable for farming.

There they established small communities of people from the same geographic

region in America. This photograph gives an idea of the appearance of the

countryside in which the settlers began their new lives.

St. Paul's River, Liberia, ca. 1900 Photomural from silver-gelatin print

Prints and Photographs Division

(23)

|

Information on Emigrants Settled in Liberia

|

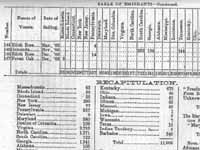

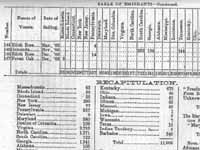

In 1867, the American Colonization Society published this

list showing the names of ships, dates of sailing, and number of emigrants

by state through December 1866. By that time, more than 13,000 blacks had

been settled in Liberia through ACS efforts. The peak years were between

1848 and 1854, when the society chartered forty-one ships and transported

nearly 4,000 colonists. After falling to the twenties in 1863 and 1864,

the numbers went up again after the Civil War, when 527 people went in 1865

and 621 in 1866. The table shows that the 3,733 Virginia emigrants were

the largest group, followed by North Carolina with 1,371, and Georgia with

1,341.

"Table of Emigrants Settled in Liberia by the American Colonization

Society," in The African Repository and Colonial Journal,

vol. 43, no. 4, April 1867, p. 117 General

Collections (24)

|

Exodus from Arkansas

|

In the spring of 1880, a group of 150 African-Americans from

Arkansas was living in temporary quarters at Mt. Olivet Baptist Chapel on

37th Street in New York before going to Liberia. Because the ACS had chartered

the only ship that regularly went to Liberia, this group, which was going

under its own auspices, was trying to charter another ship. The article

that described their circumstances, entitled "Colored Exodus from Arkansas,"

stated that another 50,000 blacks were preparing to emigrate from the Gulf

states to Arizona and New Mexico, where they planned to purchase farm land.

"Refugees awaiting transportation to Liberia at Mr. Olivet Baptist Chapel,

New York City" From, Frank Leslie's Illustrated News, April

24, 1880, p. 120 Photomural from woodcut Prints

and Photographs Division (25)

|

New Directions for the ACS

|

In 1892, the ACS abandoned publication of The African

Repository and replaced it with Liberia. The name change reflected

a new direction for the society, as announced in the first issue of Liberia.

Instead of aiding emigrants, the ACS turned its attention to the question

of "How can the society best help and strengthen Liberia?" The society committed

itself to fostering a public-school system in Liberia, promoting more frequent

ships between the U.S. and Liberia, collecting and diffusing more reliable

information about Liberia, and enabling Liberia to depend more on herself.

Future colonists were to be selected with a view to the needs of Liberia,

not their own situations. An example of this preferred type of colonist

was Miss Georgia Patton, described in an early issue of Liberia.

Well-educated, Miss Patton planned to practice medicine and teach school

in Liberia. She also shared the ACS goals of doing good for others and spreading

Christianity and civilization in Africa.

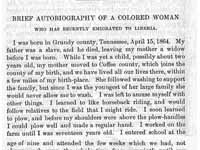

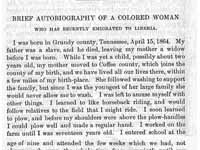

"Brief Autobiography of a Colored Woman Who Has Recently Emigrated to

Liberia," in Liberia, no. 3, November 1893, pp. 78-79 General

Collections (26)

"Dey's Mission, Liberia," ca. 1900 Photomural from silver-gelatin print

Prints and Photographs Division

(27)

|

Did Bonds Ever Reach Liberia?

|

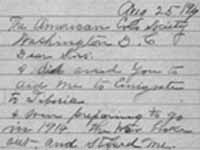

In the summer of 1919, Henry Bonds, still in the U.S. and

having moved to Tullahassee, Oklahoma, wrote the society once again about

going to Liberia. He pointed out that World War I had stopped him, but that

he still wanted to go and wanted to know if the aid promised him was still

good. A number of letters between Bonds and the ACS exist, but they do not

answer the question whether or not Bonds ever reached Liberia. Perhaps further

research could provide the answer and more information about Bonds and his

family.

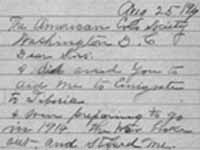

[Letter from Henry Bonds of Tullahassee, Oklahoma], August 25, 1919

Holograph American Colonization Society Papers Manuscript

Division (28)

|

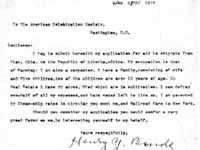

Application for ACS Help in Going to Liberia

|

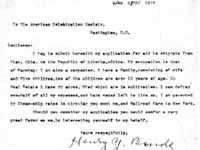

In 1912, Henry Young Bonds of Vian, Oklahoma, began correspondence

with the ACS about going to Liberia. As part of his application, Bonds sent

in this formal, notarized form. Bonds expected to defray half of the $591

he needed as passage money for himself and his family and asked the ACS

for the other part. He planned to sell his land to raise money for support

while getting established in Liberia. After a two-year application process,

Bond's request was approved by the ACS. He planned to sail in October 1914,

but was prevented from doing so by the outbreak of World War I.

[Formal application of Henry Bonds to emigrate to Liberia], 1913 Legal

document American Colonization Society Papers Manuscript

Division (29)

|

Henry Bonds Hopes to Emigrate

|

As part of his application for ACS aid in emigrating to Liberia,

Henry Bonds submitted a postcard with a photograph of his family. Left to

right are Catherine, eight; Bonds; Loretta, three; Bonds's wife Mary; and

Floyd, six. Not pictured are two unnamed older, married children, perhaps

from an earlier marriage, who did not wish to emigrate. Born in 1864 near

Guntown, Mississippi, Bonds had come to Indian Territory (now Oklahoma)

in April 1890. His wife Mary, thirty, born in Indian Territory near Tahlequah,

was educated in the Cherokee colored high school and had taught in the Vian

colored school.

[Henry Y. Bonds and family], ca. 1912 Photomural from silver-gelatin

print American Colonization Society Papers Manuscript

Division (30)

|

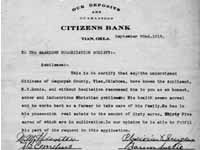

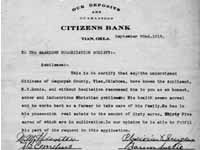

Recommendation for Liberia Applicant

|

Because the American Colonization Society was very concerned

about the character of emigrants they sent to Liberia, applicants had to

submit letters of recommendation. This highly favorable letter came from

officials of the Citizens Bank of Vian. Bonds also supplied one from J.H.

Dodd, M.D., who said that Bonds had "a host of friends in all the races"

and that his family was "regarded as one of the very best in the country."

[Letter of recommendation for Henry Bonds], 1913 American Colonization

Society Papers Manuscript Division

(31)

|

Map showing Vian, Oklahoma, and Surrounding Territory

|

Beginning in the early 1800s, Cherokees, Choctaws, and other

eastern Native American tribes signed treaties giving up southeastern land

in return for land west of the Mississippi in what became known as Indian

Territory, or even later, Oklahoma. In addition, some tribes were removed

to the areas by force. After the Civil War, the United States government

confiscated territory from Native Americans who had supported the Confederacy

and, in 1889, opened that land to other settlers. This map of the Vian area

shows land owned by Henry Bonds's children. A plot in the left corner of

section 34 and one in the lower middle are assigned to his daughter Catherine

Bonds, "N.B.F.," which stands for "new-born freedman," a term apparently

applied to blacks born after Emancipation, as well as former slaves. The

plot labelled N.B.F. 457, is also probably part of a Bonds claim. It is

unclear why the land was in the children's names.

[Map of Vian area] Indian Territory: Cherokee Nation Muskogee,

Indian Territory [Oklahoma]: Indian Territory Map Company, 1909 Photomural

Geography and Map Division

(32)

|

![[Campus of Booker T. Washington Institute in Liberia]](images/campus0.jpg)

![[Letter about ACS support for Booker T. Washington Institute]](images/support0.jpg)

ACS Supports Liberian Education [campus][letter]

|

The Booker T. Washington Institute at Kakata, Liberia, was

founded in 1929 by a group of American missionary and philanthropic organizations,

including the American Colonization Society. Like Tuskegee Institute, the

school emphasized vocational training and prepared many young Liberians

for jobs in agriculture, auto mechanics, carpentry, masonry, and other trades.

The campus of the institute was built on a 1,000-acre tract of land granted

by the Liberian government. As the accompanying letter shows, the ACS provided

funding for the institution.

Campus of Booker T. Washington Institute in Liberia, ca. 1940 Photomural

from silver-gelatin print Prints

and Photographs Division (33)

[Letter about ACS support for Booker T. Washington Institute], June

10, 1940 Typed letter American Colonization Society Papers Manuscript

Division (34)

|

![[Campus of Booker T. Washington Institute in Liberia]](images/campus0.jpg)

![[Letter about ACS support for Booker T. Washington Institute]](images/support0.jpg)

![[Previous]](prev.gif)

![[Next]](next.gif)

Library of Congress

Library of Congress