The teacher and scholar had no children of his own, but he fostered the careers

of two generations

of school administrators. Cubberley, in fact, helped create the profession. In

large part as a

result of his work, school administration parted ways with teaching, growing

into a separate field

with its own conventions and body of knowledge.

|

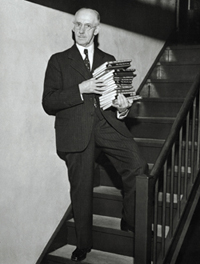

Stanford University's Ellwood P.

Cubberley is credited with

separating educational administration from the teaching profession. He

advocated the "scientific"

study of school administration.

--Stanford University

|

Cubberley, the founding father of a profession,

was paternal in other senses, too.

Though hardly remarked on in his day, his

views were riddled

with assumptions about the natural superiority of men like himself—white, Anglo-

Saxon,

native-born—and the American society they had shaped. In practical terms, the

reforms he and his

circle spurred helped ensure that women would largely remain the workers in a

system managed by

men.

Born just after the Civil War in the tiny town of Andrews, Ind., the

future leader attended

the local public schools and helped out at his father's drugstore. Because his

high school lacked a

year of the required four for admission to college, Cubberley completed a

college-preparatory

program at Purdue University.

He was cool to his father's plan that he

attend the pharmacy

school

there, but it was not until he heard David Starr Jordan, the president of

Indiana University,

lecture on "The Value of Higher Education" that he set his own course.

Cubberley entered Indiana

University with Jordan as his adviser. During his senior year, Cubberley ran

the stereopticon

lantern that often enlivened Jordan's public lectures. Handsome, friendly, and

hard-working, the

physics major made a good impression.

After a year's interruption to teach

at a one-room school

near his hometown, he earned his degree in 1891. Jordan successfully

recommended him for a science

teaching position at a small Baptist college and a little later for a similar

position at Vincennes

University, also in Indiana.

After two years as a professor there, at the

age of 25, Cubberley

was named president of the institution.

In 1896, once again thanks to his

mentor Jordan, the

young

college president moved up to become the superintendent of the San Diego public

schools. Probably

without knowing it at the time and still thinking of himself as a scientist

with a particular

interest in geology, Cubberley not only changed jobs, he also changed the focus

of his professional

life from then on.

Business as a Model

His two-year tenure in the

California district

was not smooth, and it left the former college president with a strong

sentiment against

"politicized" school boards and elected school officials.

Already an

enthusiastic student of

biological

evolution, Cubberley concluded that a similar process was at work socially. The

existing social

order was therefore the product of an objective process that weeded out

maladaptive arrangements.

Further, in the face of massive immigration and labor unrest, the urgent

mission of the schools was

to win the day for solidarity and the American way of life while preparing

individuals for their

differing destinies by class.

Reflecting the temper of the times, Cubberley

was also enamored

of

"business efficiency." He believed that the best way to achieve efficiency in

education, as in

business, was by building a multilayered organization headed by

experts.

"Cubberley had an

intensely hierarchical view of leadership,'' with little room for

decisionmaking by teachers, write

David B. Tyack and Elizabeth Hansot in their comprehensive 1982 account of

public school

leadership,

Managers of Virtue.

Craving a wider scope for his talents, Cubberley

in 1898 accepted an

appointment to Stanford University, which was then headed by his old mentor,

Jordan. Though he had

never taken an education class and had no advanced degree, Cubberley became the

second professor in

the new education department, with orders to make the field respectable or face

closing up shop.

The energetic and organized Cubberley not only saved the department, he also

remade himself into

a fit head for it, earning master's and doctoral degrees at Teachers College,

Columbia University,

during leaves from Stanford. At the same time, he began to formulate a program

for the

"scientific''

study of school administration and met other educators who were to form his

intellectual

circle.

Widespread Influence

Entrenched school bureaucracies and

the "tracking" of

students in

high schools have their roots in the successes of Cubberley and other members

of the informal

network of academics, foundation leaders, and urban school superintendents that

held the greatest

sway in American education from about 1910 to 1930. Like Cubberley, many of

them attended graduate

school at Teachers College in the early years of the century.

In time,

Cubberley became a

renowned author and consultant, carrying his message of social improvement to

the nation. In the

midst of public lectures, teaching, and scholarship, he found the time to

propose and edit the

first

widely used series of textbooks in education—106 of them, 10 written by

Cubberley himself.

And

he

published in 1919 what for many years was the standard history of American

education, Public

Education in the United States.

In California, "Dad" Cubberley's

influence was widespread.

Eventually stepping up to dean of the education school at Stanford, he advised

on professional and

policy matters related to education, and he helped dozens of graduates find

jobs through his

personal connections—a power one observer likened to that of New York City's

Tammany Hall

politicians.

Much of that activity was profitable, and Cubberley invested

well. He enjoyed a

comfortable life with his wife, Helen, provided for her after his death in

1941, and in the end

gave

more than $360,000 to his beloved Stanford University for a new building to

house the school of

education.

The leadership ideal that Cubberley held and embodied was, in

Tyack and Hansot's term,

"an educational Teddy Roosevelt''—charging up the San Juan Hill of ignorance

one minute, gracious

to

women, children, and subordinates in the next.

The image, however, cannot

comfortably stretch to

cover non-European men, or lay people, or women, and the dean led the way in

disparaging the very

electoral processes that were most likely to bring outsiders to the

decisionmaking table.

Cubberley's influence was profound for a half-century, but by the 1970s, his

outlook and many of

his ideals seemed hopelessly outdated and undemocratic. What the education

historian Lawrence A.

Cremin called the "wonderful world'' of Ellwood P. Cubberley had dimmed at

last.