|

|

December 15, 1999

Featured Profiles

Marva Collins | Rudolf Flesch | Steve Jobs

Felicitas and

Gonzalo

Mendez | Ella Flagg Young

Ahead of Her Time:

Ella Flagg Young

|

When Ella

Flagg Young took office as the

elected superintendent of

the Chicago schools in 1909, she confidently declared that

"in the near future, we

|

|

Chicago Historical Society

|

will have more women than men in executive charge of the vast

educational system." But,

in fact, for more than 60 years Young remained almost alone in

her achievement, one of a

very few women with enough political clout and experience to land

the top job in a large

district. Just as extraordinary, both as Chicago superintendent

and as president of the

National Education Association-the first woman to hold either

post- Young promoted an

ideal of teacher power and school democracy radically at odds

with the views of many of

her prominent colleagues.

Born in 1845, Young attended school for only a few years,

though her working-class

parents encouraged her independence of mind and spirit. At 17,

after attending normal

school, she took her first teaching job. Her pupils were the

young men who herded cattle

on the outskirts of Chicago. She married at 23, but became a

widow soon after. Young

eventually rose to become principal of the system's largest high

school before being named

assistant superintendent in 1887.

At the age of 50, she took a seminar with the philosopher and

educator John Dewey, who

was then teaching at the University of Chicago. The two began a

rich collaboration, with

Young using her own experience to test Dewey's ideas. After

resigning from the school

system in 1899 because she disagreed with the autocratic approach

of the new

superintendent, Young earned her doctorate under Dewey.

In 1905, she became the director of the Cook County Normal

School, continuing her close

association with teachers. Teachers and suffragists, using the

vote women won for Illinois

school elections in 1891, helped Young win the race for

superintendent, and in 1910 she

also became president of the male-dominated NEA.

Her tenure as superintendent was marked not only by reforms

but also by battles with

school board members. After seven turbulent years on the job,

Young retired, remaining

active in education and politics until her death in 1918.

—Bess Keller |

'Regardless of

Lineage':

Felicitas and Gonzalo Mendez

|

| When their children were turned away from

an all-Anglo school in

Orange County, Calif., and told to go to a school for Mexican-

Americans, Felicitas and

Gonzalo Mendez fought back.

In 1945, the farming couple filed

a lawsuit on behalf of

5,000 Latinos against the county's four school districts, seeking

the right for their

children to be educated in the same school as Anglo children.

Felicitas Mendez, a native of Puerto Rico, managed the

family's rented, 40-acre

asparagus farm so that her husband, a Mexican immigrant, could

work on the cause full

time. Thurgood Marshall, then the top lawyer for the National

Association for the

Advancement of Colored People, filed a friend-of-the-court brief

in the case.

A federal judge in 1946 ruled in favor of the Latinos,

rejecting the argument that the

schools for them and for Anglos were "separate but

equal." Judge Paul J.

McCormick wrote that "the paramount requisite in the

American system of public

education is social equality. It must be open to all children by

unified school

association regardless of lineage."

Though the school districts had argued that they segregated

Latino children because of

language differences, the judge pointed out that the districts

didn't even test all

children on their language ability.

Judge McCormick's decision was upheld on appeal a year later,

launching integration of

schools in Orange County. And while the case showed that

segregation was not just an issue

for African-Americans, it helped point the way to the U.S.

Supreme Court's historic 1954

decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka.

Gonzalo Mendez died in 1964, and Felicitas Mendez in 1998.

—Mary Ann Zehr |

A Letter to

Johnny's Mom:

Rudolf F. Flesch |

| Nearly 45 years after Rudolf Flesch created

a fictional 12-year-old

boy and held him up as an indictment of elementary education in

the United States, Why

Johnny Can't Read is still used as ammunition in the battle

over how children should

be taught to read. In the book, Flesch, a writer and

consultant who had emigrated from

Austria in 1938, advocated the phonics method of instructing

children in the alphabet and

basic sounds. He likened learning to read to learning to drive.

In both, he argued,

students must first learn the basics-the mechanics of a car or

the mechanics of the

language-before taking the driver's seat.

The problem with the reading instruction most U.S. students

received at the time,

Flesch believed, was that few of them were learning those initial

skills.

"The teaching of reading-all over the United States, in

all the schools, in all

the textbooks-is totally wrong and flies in the face of all logic

and common sense,"

he wrote in the 1955 volume.

"Johnny's only problem was that he was unfortunately

exposed to an ordinary

American school."

The book begins with a letter to Johnny's mother, and includes

lessons and step-by-step

instructions for parents.

A commercial success in its time, the book has become a

manifesto for parents seeking a

return to "the basics" in reading instruction.

But it has angered many educators, who say it endorses the

kind of drilling in letters

and sounds that they contend impedes real learning and takes the

fun out of reading.

Flesch repeated his arguments in his 1981 sequel, Why

Johnny Still Can't Read,

in which he included what he said were alarming new statistics on

illiteracy.

The original "Johnny" book has been reprinted

several times, most recently in

1994. Other books by Flesch, who died in 1986 at age 75, also

focused on the use of

language and literacy. In all his volumes, he promoted his own no-

nonsense style, as

evident in the titles: The Art of Plain Talk, How to

Make Sense, The Art

of Clear Thinking, and Say What You Mean.

—Kathleen Kennedy Manzo |

Doing

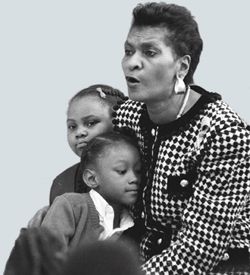

Things Her Way:

Marva Collins

|

|

From the start, Marva Collins made no secret of her dismay with what

she considered the poor

quality and attitudes of Chicago's teachers. Determined to go her own

way in educating the poor,

inner-city children she believed were being ignored by a callous

system, she quit her job as a

teacher in the city's public schools to open her own private school

in 1975.

|

|

Benjamin Tice Smith

|

In it, Collins preached self-respect, success, and self-reliance.

She insisted that her students

read, read, read. She advocated the use of phonics and salvaged some

of her first textbooks from a

garbage dump at a Chicago public school.

The Westside Preparatory School, housed in the basement of a

community college, soon became one of

the best-known schools in the country. Visiting reporters watched as

children who had been labeled

failures by the public schools recited passages of Shakespeare and

wrote letters to heroes of Greek

mythology.

Her determination-and the success of her students-earned her a spot

on the newsmagazine show "60

Minutes." In 1980, Collins' message of academic rigor and self-

reliance caught the attention of

President-elect Ronald Reagan's transition team. But Collins turned

down an offer to become U.S.

secretary of education. Instead, she has gone on to train teachers

nationwide in her methods, lend

her name to both public and private schools, and write four books.

Despite the acclaim, Chicago teachers remained critical of her

success, questioning her results in

bitter attacks that prompted Collins to defend herself on the Phil

Donahue television show in 1982.

Collins was born in Monroeville, Ala., in 1936. Though she came from

a prominent family, she was

denied access to the local public library because she was black. She

graduated from the all-black

Escambia County Training School in Atmore, Ala., and from Clark

College in Atlanta.

In Chicago, where she began her teaching career in 1961, Collins

became known as a maverick and

troublemaker. Determined to do it, as she titled her autobiography,

Marva Collins' Way, she came to

embody a firm but friendly style of teaching that has proven

effective with disadvantaged students.

"In each classroom, we have a mirror," she says, "and the little

ones, each time they walk by, have

to hug themselves and say, 'I am wonderful. I am marvelous.'

"

—Ann Bradley

|

An Apple for

the

Classroom:

Steven Jobs

|

|

Steven Jobs did more than any of the other young firebrands of

Silicon Valley in the early 1980s to

convince the world that the personal computer could be an essential

tool for every man, woman, and

ultimately, child. That vision helped move computers-especially his

Apple II and Macintosh

computers-into nearly every school and ignited a technology buying

spree by U.S. educators that

continues to this day.

It was far from a pure triumph, though. Jobs' mercurial, divisive

style in helping run Apple

Computer Inc. made the company weaker as it faced mounting

competition from ibm and other companies

entering the budding PC market.

And many educators who became Apple loyalists were more impressed by

Stephen Wozniak, the brilliant

co-founder of the company who invented the first Apple computer and

the Apple II.

Born in 1955 and adopted by a family that later moved to Los Altos,

Calif., Jobs was a high school

friend of the older Wozniak, an electronics genius. In 1977, Wozniak

and Jobs, along with Mike

Markkula, incorporated Apple Computer, for a while based in Jobs'

garage.

With brash marketing led by Jobs, Wozniak's elegant machines caught

the first wave of popular

enthusiasm for microcomputers. Jobs' vision of the computers as

appliances for everyman played well

in the media and helped attract exceptional talent to the company.

The Apple II won the hearts of thousands of teachers in the 1980s, in

part because the company

offered schools its best computers, practical software, and free

computer course materials. The

giant International Business Machines Corp., by contrast, initially

offered the school market the

underpowered PC Jr., with little support.

Apple was also unmatched in its discounted pricing schemes, its

extensive support for software

development and research, and its conferences and training that

catered to educators.

In 1983, Jobs took over the development of the Macintosh computer,

but caused a schism in the

company between the Macintosh and Apple II divisions. In 1985, Apple

Chief Executive Officer John

Sculley engineered the ouster of

Jobs, who resigned and started another computer company, NextStep,

which was considered a failure.

A year later, Jobs bought a stake in the successful movie company

Pixar Animation Studios.

When Apple foundered in the 1990s, Sculley's successor, Gil Amelio,

brought Jobs back as a

consultant, only to see the Apple board of directors pick Jobs to

displace him as interim ceo in

1997. Apple has seen a recovery under a more mature Jobs, with

popular new lines of computers and

the reappearance of the friendly media buzz that the company once

enjoyed. —Andrew Trotter |

© 1999 Editorial Projects in Education  Vol. 19, number 16, page web only Vol. 19, number 16, page web only

|